Categories: "Art of translation"

Translating humor, part I

One of the most popular second-year Russian textbooks is “Russian Stage Two: Welcome Back!” One of the things that is nice about the book is that it is accompanied by a well-produced and engaging video that gives a plot arc to the text. In class my students and I came across a couple lines in the video that lacked the same punch in English that they had in Russian. A student asked how we should go about that type of translation. What a great question! Here's the context.

Lena and Tanya are talking on the phone. Lena asks Tanya how her thesis is coming along. Tanya, distracted by her wedding plans, at first does not recognize what Lena is talking about, which reinforces the video's presentation of Tanya's character as somewhat flakey. The lines go like this:

| Лена: Как твои дела? Как твоя дипломная работа? | Lena: How are you? How is your thesis coming? |

| Таня: Какая работа? Ах, дипломная? Всё нормально. | Tanya: What kind of work? Ah, my thesis. Everything's okay. |

The performance of the dialog is slightly humorous in Russian. The Russian phrase for thesis is «дипломная работа», which literally means “diploma work.” Thus when Tanya doesn't quite make out the word «дипломная» but does make out the word «работа», she can ask «Какая работа?» “What kind of work”, then figure it out in her head and say “Ah, diploma work.”

Why does the translation not capture the humor of the original? It fails because in English ‘thesis’ has no obvious connection to “what kind of work?” Ideally a translation intended for a general audience will capture the emotional content (in this case the humor) as well as the informational content. So how do you go about the process of figuring it out? Here is how our discussion went.

Step 1: identify the sources of the humor. In this case the humor stems from a variety of things, including the inherent relationship between «какая работа» and «дипломная работа». «Какая» is one of the things you can say in Russian when you didn't quite catch what the other person has said. Tanya didn't at first figure out what Lena said because she was distracted by wedding invitations, or, alternatively, she didn't understand Lena because Lena's headcold made it tougher.

Step 2: identify the things you can't change in the translation. «Дипломная работа» has a standard equivalent in English, which is ‘thesis.’ Not much you can do about that.¹

Step 3: identify the things you can change and brainstorm on them. In English there are a lot of ways you can ask for additional information when you didn't quite hear what someone said. Let's brainstorm those phrases:

- Could you repeat that, please?

- Excuse me?

- Come again?

- Speak more clearly!

- Huh?

- What did you say?

- What's that?

- What was that?

- Say what?

- My what?

Somehow we have to find a variation on one of those phrases that has some obvious connection to ‘thesis.’ In a previous blog entry we discussed the word whatchamacallit. Among the variations there were whoziwhatsis and whatsis, the last three letters of which match the word thesis. Ah, there we have it!

| Lena: How are you? How is your thesis coming? |

| Tanya: My whatsis? Oh, my thesis! Everything's okay. |

When we reached this point in our class discussion, the whole class laughed, which meant we had a successful connection. Of course, this version is funny for an additional reason: whatsis is a very informal word, one that doesn't quite match the neutral tone of the rest of the conversation.

One last thought. Humor is best when it is spontaneous and not overanalyzed. If nothing here seemed particularly humorous, chalk it up to the academic discussion. It really was funny at the time... but you probably had to be there.

¹ Okay, I'm fudging here. You could also say ‘senior project.’

Ассортимент

Last summer in Kazan I was at a little restaurant with a friend, and after dinner we ordered tea, and to complement it we ordered a little plate containing «сухофрукты в ассортиментe» ‘assorted dried fruits.’

They also offered a plate containing «конфеты в ассортименте» ‘assorted candy.’

Ah, what a joy! Eat a full meal, and then rest a bit, have a bit of tea, and see what space opens up for a bit of dried apricot or an almond or a bit of chocolate. «Ах, какая благодать!» “Oh, what bliss!”

Thus we see that the word for ‘assortment’ in Russian is ассортимент, which declines like this:

| Sg | Pl | |

| Nom | ассортимент | ассортименты |

| Acc | ||

| Gen | ассортимента | ассортиментов |

| Pre | ассортименте | ассортиментах |

| Dat | ассортименту | ассортиментам |

| Ins | ассортиментом | ассортиментами |

It can be used as a noun in the meaning of ‘assortment’ or ‘range’ or ‘number’:

| В этом ресторане большой ассортимент мясных блюд. | This restaurant has a large assortment of meat dishes. |

| В этом году наша фирма расширяет ассортимент высококачественных товаров на пятьдесят процентов. | This year our company is expanding our range of high-quality goods by fifty percent. |

In English we might buy a box of ‘assorted chocolates,’ or an organic farm might offer weekly boxes of ‘assorted vegetables.’ The Russian equivalent of ‘assorted’ is the prepositional phrase «в ассортименте», literally ‘in an assortment.’ Thus we have:

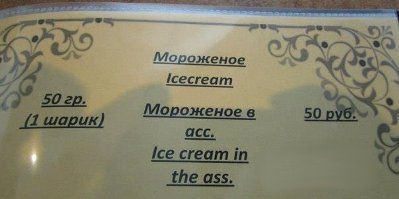

| мороженое в ассортименте | assorted flavors of ice cream |

| вино в ассортименте | assorted wines |

| цветы в ассортименте | assorted flowers |

Let's assume that you are in a Russian restaurant, and their menu offers assorted flavors of ice cream, and let's assume they are trying to make their menu tourist-friendly. They could put it like this:

But you know, ассортимент is kind of a long word, and a menu only has so much space, and sometimes translators are not entirely aware of the cultural equivalents of what they want to say, so sometimes we get odd results. Consider this menu that someone found during the recent Sochi Winter Olympics:

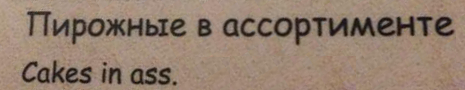

Alas, I wish I could say that this was the only occurence, but there was also

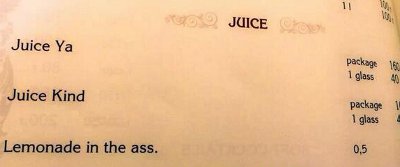

and also

I imagine that after these menus hit the net, the translator must have felt like an ... Oh, never mind.

«Зарулила я в бутик»

Over a year ago I posted an entry on the words блузка/кофта that included a translation contest. Then I headed to Russia and lost track of it. Finally here are the results. The original and somewhat vulgar poem is posted here.

The best translation was submitted by D. Preker, and the first runner up was B. Schilke. Both translations are posted here.

PS to D. Preker. The e-mail address you originally wrote from is no longer valid. Send my your mailing address to collect your prize money. Specify the e-mail address from which you originally sent the translation as well so I know it's the real you.

Тот

The Russian word for ‘that,’ as in “that car,” “that dog” or “that house” is тот. Grammatically it is a demonstrative adjective, thus it occurs in forms that vary for case, number, and gender, and of course it agrees with the noun it modifies. It declines like this:

| Masc | Neut | Fem | Pl | |

| Nom | тот | то | та | те |

| Acc | * | ту | * | |

| Gen | того | той | тех | |

| Pre | том | |||

| Dat | тому | тем | ||

| Ins | тем | теми | ||

Here are some sample sentences:

| — Кто живёт в том доме? — Вампир. Туда не ходи. |

“Who lives in that building?” “A vampire. Don't go there.” |

| В том году мы жили в Уфе. | That year we lived in Ufa. |

| На той планете никогда не было настоящей атмосферы. | There never was a real atmosphere on that planet. or That planet never had a real atmosphere. |

In English the difference between ‘this’ and ‘that’ is essentially distance. Theoretically the same thing is true in Russian, but somehow the distance factor is not quite the same in these languages. Truth to tell, I haven't come up with a proper explanation of the difference, but here are my current hypotheses:

English

- If something is close to me, I use ‘this.’

- If something is close to you, I use ‘that.’

- If something is far from both of us, I use ‘that.’

Russian

- If something is close to me, I use «этот».

- If something is close to you, I use «этот».

- If something is far from both you and me but I can use a gesture (either hands or a glance) to point it out and we can both clearly see it, I use «этот».

- If something is far from both you and me and it is partially blocked by intervening items, I use «тот».

- If something is far from both of us and not visible but we have spoken about it before, I use «тот».

In other words, there are quite a few contexts where even этот is best translated as ‘that’ in English. For instance, let's say your Russian friend sees you reading a book and wants to know the name of the book, the question will most likely come out like this:

| Как называется эта книга? | What's the name of that book? |

If you and a Russian friend are standing on the sidewalk looking at a building across the street. If your friend points to the building and inquires who lives there, then it's most likely to come out like this:

| Кто живёт в этом доме? | Who lives in that building? |

If you and your Russian friend are talking about a building in the distance that is partially blocked by other buildings, you will most likely use «тот»:

| — Кто живёт в том доме? — В каком? — Вон в том с красной крышей, за церковью.» |

“Who lives in that building?” “In which one?” “There in that one, the one with the red roof behind the church.” |

And if you can't see the building but you've discussed it before, «тот» is best:

| Кто живёт в том деревянном доме на Садовой улице? Помнишь, мы о нём говорили, там ещё такая злая собака, лает без умолку. Не знаю как соседи бедные спят | Who lives in that building on Sadovaya Street? You remember, we talked about it. There's a really mean dog there that never stops barking. I don't know the poor neighbors manage to sleep. |

In short, one cannot mechanically say that этот always corresponds to ‘this,’ and тот always corresponds to ‘that.’ You will need practical experience wth Russian life to start getting a feel for the contexts where each is used.

BTW, I'm actively on the lookout for better explanations of the this/that этот/тот distinction. Please feel free to express disagreements, corrections, or other insights in the comments. We are all here to do a better job at cross-cultural communication, so your input will be appreciated.

Переводить/перевести

The verb pair переводить/перевести means ‘to translate’ and is conjugated like this:

| Imperfective | Perfective | |

| Infinitive | переводить | перевести |

| Past | переводил переводила переводило переводили |

перевёл перевела перевело перевели |

| Present | перевожу переводишь переводит переводим переводите переводят |

No such thing as perfective present in Russian. |

| Future |

буду переводить будешь переводить будет переводить будем переводить будете переводить будут переводить |

переведу переведёшь переведёт переведём переведёте переведут |

| Imperative | переводи(те) | переведи(те) |

This is a typical transitive verb; that is, it has a do-er (grammatical subject) that occurs in the nominative case, and a done-to (grammatical direct object) that occurs in the accusative case:

| Кто перевёл эту статью? | Who translated this article? |

| Что ты переводишь? | What are you translating? |

The language you are translating from appears in the genitive case after the preposition с and the language you are translating to appears in the accusative case after the preposition на:

| Переведите эту статью на английский к понедельнику. | Translate this article into English by Monday. |

| — С какого языка перевели «Преступление и наказание»? — С русского, конечно. |

“What language was ‘Crime and Punishment’ translated from?” “From Russian, of course.” |

| Хотя он сам русский, Набоков писал «Лолиту» по-английски. То есть, потом пришлось перевести её с английского на русский. | Although he himself is a Russian, Nabokov wrote ‘Lolita’ in English. That is, later it had to be translated from English into Russian. |

| — Этот софт перевёл «ни пуха, ни пера» как «neither fuzz nor feather». Что за чушь? — Это дословный перевод. Правильный перевод — «good luck». |

“The software translated ‘ни пуха, ни пера’ as ‘neither fuzz nor feather.’ What kind of nonsense is that?” “That's a word-for-word translation. The correct translation is ‘good luck.’” |

So how would you say in Russian “How do you translate ‘обезьяна’ into English?” A beginning Russian student named Hiram with good study habits would probably say “Как ты переводишь «обезьяна» на английский?” That's a perfectly grammatical translation. The Russians would understand the translation. But it's not the way they would normally say it. For those kind of generic questions the Russians usually use either indefinite personal constructions, that is, verbs in the present tense они form, or infinitive constructions. So theoretically one could say:

| Как переводят «обезьяна» на английский? | How do you translate ‘обезьяна’ into English? |

That is a perfectly grammatical construction, and it's definitely better than Hiram's original translation, but the infinitive constructions are better yet:

| Как перевести на английский «обезьяна»? | How do you translate ‘обезьяна’ into English? |

Even better are phrases that don't use ‘to translate’ at all:

- How do you say ‘обезьяна’ in English?

- Как сказать по-английски «обезьяна»?

Как по-анлглийски будет «обезьяна»?

Как по-анлглийски «обезьяна»?

And when you combine that with the answer, you get short dialogs like this:

| — Как по-английски будет «обезьяна»? — «Обезьяна» будет «monkey» или «ape». |

“How do you say ‘обезьяна’ in English? “‘Monkey’ or ‘ape.’” |

| — Как сказать по-английски «обезьяна»? — «Monkey» или «ape». |

“How do you say ‘обезьяна’ in English? “‘Monkey’ or ‘ape.’” |

| — Как по-английски «обезьяна»? — «Monkey» или «ape». |

“How do you say ‘обезьяна’ in English? “‘Monkey’ or ‘ape.’” |