Ассортимент

Last summer in Kazan I was at a little restaurant with a friend, and after dinner we ordered tea, and to complement it we ordered a little plate containing «сухофрукты в ассортиментe» ‘assorted dried fruits.’

They also offered a plate containing «конфеты в ассортименте» ‘assorted candy.’

Ah, what a joy! Eat a full meal, and then rest a bit, have a bit of tea, and see what space opens up for a bit of dried apricot or an almond or a bit of chocolate. «Ах, какая благодать!» “Oh, what bliss!”

Thus we see that the word for ‘assortment’ in Russian is ассортимент, which declines like this:

| Sg | Pl | |

| Nom | ассортимент | ассортименты |

| Acc | ||

| Gen | ассортимента | ассортиментов |

| Pre | ассортименте | ассортиментах |

| Dat | ассортименту | ассортиментам |

| Ins | ассортиментом | ассортиментами |

It can be used as a noun in the meaning of ‘assortment’ or ‘range’ or ‘number’:

| В этом ресторане большой ассортимент мясных блюд. | This restaurant has a large assortment of meat dishes. |

| В этом году наша фирма расширяет ассортимент высококачественных товаров на пятьдесят процентов. | This year our company is expanding our range of high-quality goods by fifty percent. |

In English we might buy a box of ‘assorted chocolates,’ or an organic farm might offer weekly boxes of ‘assorted vegetables.’ The Russian equivalent of ‘assorted’ is the prepositional phrase «в ассортименте», literally ‘in an assortment.’ Thus we have:

| мороженое в ассортименте | assorted flavors of ice cream |

| вино в ассортименте | assorted wines |

| цветы в ассортименте | assorted flowers |

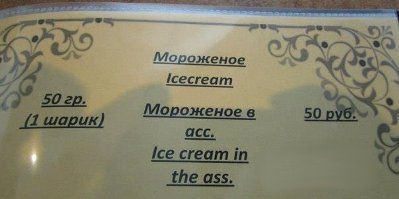

Let's assume that you are in a Russian restaurant, and their menu offers assorted flavors of ice cream, and let's assume they are trying to make their menu tourist-friendly. They could put it like this:

But you know, ассортимент is kind of a long word, and a menu only has so much space, and sometimes translators are not entirely aware of the cultural equivalents of what they want to say, so sometimes we get odd results. Consider this menu that someone found during the recent Sochi Winter Olympics:

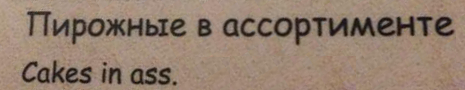

Alas, I wish I could say that this was the only occurence, but there was also

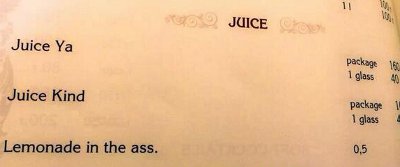

and also

I imagine that after these menus hit the net, the translator must have felt like an ... Oh, never mind.

Колокол

The Russian word 'колокол' means 'bell'. It is a noun that is first syllable stressed in the singular. In the plural form of the word the grammatical ending is stressed:

| Sg | Pl | |

| Nom | кoлокол | колокола |

| Acc | колокол | колокола |

| Gen | колокола | колоколов |

| Pre | колоколе | колоколах |

| Dat | колоколу | колоколам |

| Ins | колоколом | колоколами |

Here are a few sample sentences:

| Колокол Свободы находится в Филадельфии. | The Liberty Bell is in Philadelphia. |

| Ты видел, как он звонил в церковный колокол в воскресенье? | Did you see him ring the church bell on Sunday? |

| Иногда, когда вы слушаете внимательно, вы можете услышать колокол старой башни с часами из соседнего города. | Sometimes, when you listen closely, you can hear the bell in the old clock tower in the nearby town. |

| Митя любил слушать звон колоколов. | Mitya loved to hear the chime of the bells. |

Photo Credit: Dennis Jarvis (RussiaB_2829 - Tsar Bell) [CC-BY-SA-2.0], via Wikimedia Commons

The Tsar Bell in Russia is the largest bell in the world. It weighs 201,924 kilograms (445,170 lb), and it is 6.14 meters (20.1 ft), tall. In comparison, the Liberty Bell in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania weighs only 900 kilograms (2,080 lb), and is only 1.5 meters (5 ft) tall. The Tsar bell could make any bell seem small in comparison though. It is made completely out of bronze, although it's hard to tell being that it's completely oxidized due to age. It has never been rung because it was broken during the metal casting. If it had been rung, it would have been extremely loud, and probably would have given anyone standing near it severe hearing loss. Unfortunately, it never got to be put in the clock tower, but it can be seen at the Kremlin in Moscow. It is decorated with beautiful relief images of angels, saints, Empress Anna, and Tsar Alexey.

Водить

There is a subset of verbs in Russian that in the US are sometimes taught as verb triplets instead of pairs. You can find a list of those verbs here, and a rough summary of how those verbs are used here. Among them is the multidirectional verb водить, which conjugates like this:

| Imperfective | |

| Infinitive | водить |

| Past | водил водила водило водии |

| Present | вожу водишь водит водим водите водят |

| Future |

буду водить будешь водить будет водить будем водить будете водить будут водить |

| Imperative | води(те) |

We can say that the verb means ‘to lead [someone somewhere by your own power].’ But to be honest we normally translate it as ‘to take’ in English. For instance...

| Я вожу дочку в школу каждое утро. | I take my daughter to school every day. |

| Каждый вечер папа водит соседа в кафе. Там играют в шахматы. | Every evening dad takes the our neighbor to a cafe where they play chess. |

Generally speaking the verb means that you are taking someone somewhere but not using a vehicle to get there. It can also be used if a vehicle is involved but the vehicle is not germane to the discussion. For instance, in the following sentence, the person speaking may live near the Kremlin Armory (so they can walk there with their guests), or they may just live somewhere within the city limits, but the fact that they will take the subway to get to the armory is simply not relevant to the story.

| Мы часто водим гостей в Оружейную палату. | We often take guests to the Kremlin Armory. |

Водить can also mean to lead people around a place (random motion inside a prescribed area). In this meaning the preposition по + the dative case is used. For instance:

| Моя сестра — доцент. Она водит посетителей на эксурсии по Третьяковской галерее. | My sister is a docent. She takes visitors on excursions around the Tretyakovsky Galery. |

| Мой брат был эксурсоводом. Он водил туристов по городу. | My brother was a tour guide. He used to show people around the city. |

In the past tense the verb can also mean to take someone somewhere, and the implication is that they are no longer located at the location you mentioned.

| Я вчера водил бабшуку на почту. | Yesterday I took grandma to the post office |

| Я вчера водил своих девушек на престижную дискотеку. Вау, как им там понравилось! Я произвёл на них неизгладимое впечатление. | Yesterday I took my ladies to a classy club. Wow, they really liked it! I made a huge impression on them. |

Мусор

The Russian word мусор is a noun that means ‘trash.’ It is a first declension noun. It is never used in the plural.

| Sg | |

| Nom | мусор |

| Acc | мусор |

| Gen | мусора |

| Pre | мусоре |

| Dat | мусору |

| Ins | мусором |

Here are some examples:

| Вынеси мусор, пожалуйста. | Take out the trash please. |

| В мусорном ящике нет мусора. | There's no trash in the trash can. |

| Брось скорлупу в мусор. | Throw the eggshells in the trash. |

Russia, like many countries, disposes of their nation's trash by means of landfills. Being that Russia makes up 1/8 of the Earth's landmass they should have no problem finding places to dispose of trash, at least that's what many people in the government and waste management industry believed. That notion came to a screeching halt once a lot of the landfills started filling up. The fact that most of these full landfills are located on the outskirts of cities and towns raised the stakes even higher. It has posed a lot of problems to both the infrastructure and the nearby residents. As the amount of trash increases, the air and soil quality surrounding the landfill decreases. This makes for very unhealthy and stinky conditions. Nobody wants to step outside their house on their way to work just to be greeted by a big whiff of last year's dinner. I'll pass on those leftovers, thank you very much. The waste management industry is working with the government to find an reasonable solution. It's a work in progress, but until it gets resolved, plug your nose.

Interestingly enough, the word «мусор» is also used as a derogatory name for policemen in Russia. It's equivalent to calling a police officer 'pig' in the United States. I do not recommend using this slang within earshot of any law enforcement officer, because it'll probably get you into a pretty nasty situation. When used in this manner the word does have a plural form: «мусора».

Here are some examples:

| Не едь по Калинина, там мусора.¹ | Don't take Kalinin Street: the pigs are there. |

| Не превышай скорость по Вишневского, а то мусора оштрафуют. | Don't speed on Vishnevsky Street, otherwise the pigs will ticket you. |

¹ The word едь is substandard Russian speech, not something that a foreigner should emulate. But if a Russian is going to be rude enough to call the police мусор, then he'll probably allow himself this kind of grammatical irregularity as well, so I think we'll keep the example as it stands.

Путешествовать

One of the Russian words that can be translated as ‘to travel’ is путешествовать. It conjugates like this:

| Imperfective | Perfective | |

| Infinitive | путешествовать | попутешествовать |

| Past | путешествовал путешествовала путешествовало путешествовали |

попутешествовал попутешествовала попутешествовало попутешествовали |

| Present | путешествую путешествуешь путешествует путешествуем путешествуете путешествуют |

No such thing as perfective present in Russian. |

| Future |

буду путешествовать будешь путешествовать будет путешествовать будем путешествовать будете путешествовать будут путешествовать |

попутешествую попутешествуешь попутешествует попутешествуем попутешествуете попутешествуют |

| Imperative | путешествуй(те) | попутешествуй(те) |

In some senses this verb is exactly like the English verb ‘to travel’:

| Моя бабушка не любит путешествовать. | My grandmother doesn't like to travel. |

| Ты часто путешествуешь? | Do you travel often? How often do you travel? |

| В прошлом году я всё лето путешествовал. | Last year I traveled the whole summer. |

| — Какие планы у тебя на лето? — Я всё лето буду путешествовать. |

“What are your plans for the summer?” “I'm going to travel all summer long.” |

One difference between this verb and the English verb ‘to travel’ is that in English we talk about traveling to a place. In Russian you can't use в + accusative or на + accusative with путешествовать. Instead you talk about traveling ‘around’ a place. In that sense we use по + dative:

| В прошлом году я путешествовал по Европе. | Last year I traveled around Europe. |

| — Какие у тебя планы на лето? — Я буду путешествовать по Норвегии. |

“What are your plans for the summer?” “I will be traveling around Norway.” |

| — Ты любишь путешествовать за границей? — Нет, больше всего я путешествую по местам, которые я уже знаю. |

“Do you like to travel abroad?” “No, I mostly like to travel around places I already know.” |