Categories: "Orthography"

Ассортимент

Last summer in Kazan I was at a little restaurant with a friend, and after dinner we ordered tea, and to complement it we ordered a little plate containing «сухофрукты в ассортиментe» ‘assorted dried fruits.’

They also offered a plate containing «конфеты в ассортименте» ‘assorted candy.’

Ah, what a joy! Eat a full meal, and then rest a bit, have a bit of tea, and see what space opens up for a bit of dried apricot or an almond or a bit of chocolate. «Ах, какая благодать!» “Oh, what bliss!”

Thus we see that the word for ‘assortment’ in Russian is ассортимент, which declines like this:

| Sg | Pl | |

| Nom | ассортимент | ассортименты |

| Acc | ||

| Gen | ассортимента | ассортиментов |

| Pre | ассортименте | ассортиментах |

| Dat | ассортименту | ассортиментам |

| Ins | ассортиментом | ассортиментами |

It can be used as a noun in the meaning of ‘assortment’ or ‘range’ or ‘number’:

| В этом ресторане большой ассортимент мясных блюд. | This restaurant has a large assortment of meat dishes. |

| В этом году наша фирма расширяет ассортимент высококачественных товаров на пятьдесят процентов. | This year our company is expanding our range of high-quality goods by fifty percent. |

In English we might buy a box of ‘assorted chocolates,’ or an organic farm might offer weekly boxes of ‘assorted vegetables.’ The Russian equivalent of ‘assorted’ is the prepositional phrase «в ассортименте», literally ‘in an assortment.’ Thus we have:

| мороженое в ассортименте | assorted flavors of ice cream |

| вино в ассортименте | assorted wines |

| цветы в ассортименте | assorted flowers |

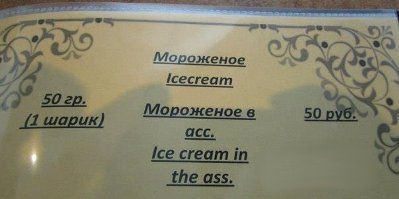

Let's assume that you are in a Russian restaurant, and their menu offers assorted flavors of ice cream, and let's assume they are trying to make their menu tourist-friendly. They could put it like this:

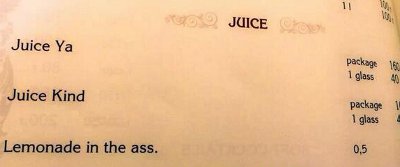

But you know, ассортимент is kind of a long word, and a menu only has so much space, and sometimes translators are not entirely aware of the cultural equivalents of what they want to say, so sometimes we get odd results. Consider this menu that someone found during the recent Sochi Winter Olympics:

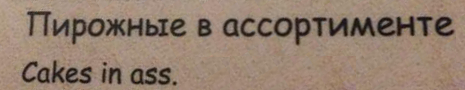

Alas, I wish I could say that this was the only occurence, but there was also

and also

I imagine that after these menus hit the net, the translator must have felt like an ... Oh, never mind.

Ё

The newest letter of the Russian alphabet is ё. Although it was first used in print in the 18th century, it didn't become an official letter until the middle of the 20th century. It's the naughtiest of Russian letters because it's the first letter of the masculine past tense form of the Russian eff word. Now of course Russian Word of the Day readers are much too cultured to bother looking up the ten thousand ridiculously creative ways the Russians use that verb and all its variants, but they should know the several euphemisms for that word that occasionally show up in conversation, particularly «ёлки-палки», a mild phrase which we can translate as “oh, fudge” or “holy moly” or “oh, crud” or “hell's bells” It can express surprise, disgust, or pain. Russians also say «ё-моё», which means roughly the same thing, but is maybe slightly less vulgar.

| Ёлки-палки! Опять написали в лифте! | Oh, hell! Someone pissed in the elevator again! |

| Ё-моё! Та секвойя должна быть высотой сто метров! | Holy moly! That redwood tree must be three hundred feet high! |

The picture you see at the right is a monument that was erected to the letter ё in the city of Ульяновск, which has about the same emotional effect as erecting a monument in the states to the letter eff. It has always surprised me that local authorities let the monument go up.

Since until relatively recently it was simply considered a variation on the letter е, sometimes dictionaries treat the letters as the same. Thus you might find the word ёж in the е section, or you might find it in its own ё section. If you have trouble finding a word with that letter, double check to see if it's in another section, or check to see whether the word is alphabetized differently than you first thought. Properly speaking, if two words differ only by е/ё, theoretically the е version should come first and the ё version should come second. If you are dealing with lists sorted by computer, be aware that there may be an additional problem. If the algorithm a program uses does not conform to the current rules, then you might unexpectedly find ё sorted before а or after я or inconsistently before/after е.

For the most part Russians don't write the double dots over the ё. It's only used in textbooks for kids and foreigners, in dictionaries, and occasionally in regular writing when otherwise the text would be ambiguous, for instance in distinguishing все “everbody” from всё “everything” or осел “settled” from осёл “donkey.” Interestingly enough, if you write the double dots in a text where people aren't expecting it, it feels awkward to the Russians and slows down their rate of reading, just as when Americans may trip over spellings like coöperation and hæmoglobin. That fact occasionally leads to rational discussions, rants and diatribes, and sometimes to amusing art:

Прописные буквы

One of the ways that Russian orthography differs from English is in its use of capital and lowercase letters. The phrases «прописная буква» and «заглавная буква» mean ‘capital letter,’ and «строчная буква» means ‘lowercase letter.’

| С прописной буквы пишется первое слово предложения. | The first word of a sentence is written with a capital letter. |

Notice that in Russian we say that a word is written "from" a capital letter (с + genitive) not "with" a capital letter.

Rules for Russian capitalization (all in Russian) are available here. One of the curious things to note is that during the Soviet period the names of holidays associated with the revolution were written with a capital letter on the first word (not the others, if any), thus: Первое мая May First, Международный женский день International Women's Day, Новый год New Year's, Девятое января January Ninth. (Why the heck they thought New Year's was a revolutionary holiday is beyond me.) Religious holidays, in keeping with the Communist Party's general denigration of religion, were supposed to be written with a lowercase letter: рождество Christmas, троицын день Trinity Day (which is usually called Pentecost in the West), святки Yuletide. That bit is changing nowadays, and the first letter of the first word of religious holidays is often capitalized. The Soviet period rules are still reflected in some places, including the link just given.

Last but not least, first names, patronymics, Western middle names, and surnames (last names) are always capitalized:

| Дмитрий Анатольевич Медведев | Dmitri Anatolievich Medvedev (current president of Russia) |

| Джордж Уокер Буш | George Walker Bush (previous President of the USA) |

| Barack Hussein Obama II | Барак Хусейн Обама II (current President of the USA) |

Picky detail: the «II» of Obama's name is said «второй» out loud.