Виза

The primary meaning of виза is visa, the document without which you cannot enter a foreign country. The US and Russia have a tit-for-tat game going on that esentially means Russians can't come to the US without obtaining a visa (which is an onerous process), and Americans can't go to Russia without going through an annoying process as well. Here's a picture of my visa for the summer, with portions grayed out for obvious reasons. It occupies an entire page of my passport:

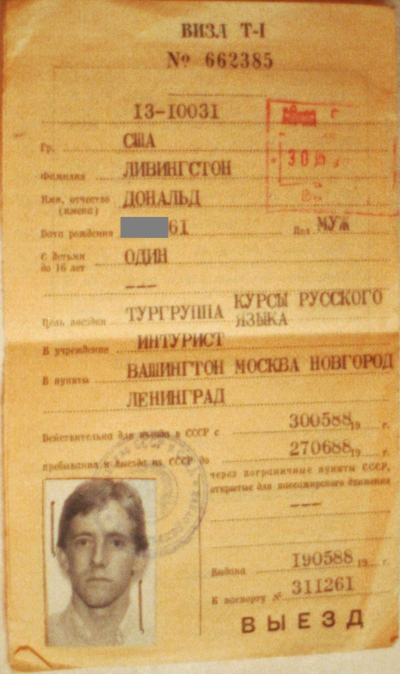

Back in the Soviet period a visa was a three-part form that was not attached to your passport. When you entered the country, they stamped the visa and removed on part. When you exited the country, they stamped and retained the rest of the visa so that once you were gone, there was no proof in your passport that you had ever been in the Soviet Union. I never quite figured out the reasons for that. Here's a photo of my visa from 1988:

Виза is a perfectly regular first declension noun:

| Sg | Pl | |

| Nom | виза | визы |

| Acc | визу | |

| Gen | визы | виз |

| Pre | визе | визах |

| Dat | визам | |

| Ins | визой | визами |

Before you get a visa to Russia, you have to get an invitation from a family, hotel or business. That's a lengthy process as well. And of course there are fees involved. Once you get to Russia, you have to register your passport/visa with internal immigration, which produces another document and involves other fees. Then by law you are required to have your visa and passport and registration on you at all times, and the police can stop you at any time and demand to see those documents. And of course if you passport, visa or registration is stolen, then it's a major pain to get them replaced. And of course there are fees involved. It's entirely amazing how many problems can crop up with these things. For instance...

| — Что случилось с твoими документами? — Я был в синагоге на богослужении, когда начался пожар. Никто не пострадал, но половина моей визы сгорела. |

“What happened to your documents?” “I was at a service in a synagogue when it caught fire. No one was hurt, but half of my visa burned up.” |

That may sound ridiculous, but it actually happened to one of my students in ’92. We were in Moscow at the time. Our visa support was in Leningrad. I ended up having to head back to Leningrad to get a new visa for him.

| — Сколько ты заплатил за визу? — Шестьсот с чем-то долларов. — Так много? — Да, ситуация была сложной, мне пришлось доплатить за срочное оформление. |

“How much did you pay for your visa?” “Six hundred plus dollars.” “That much?” “Yes, it was a complicated situation. I had to pay extra for expedited processing.” |

That also may sound ridiculous, but in fact that's what I had to pay for the visa for this summer.

| — Что случилось с твоим паспортом и визой? — На вокзале в Ленинграде ко мне подошёл незнакомый человек, который попросил посмотреть мой паспорт. Я ему его дала, и он с ними убежал. |

“What happened to your passport and visa?” “At the train station in Leningrad a stranger walked up to me and asked to see my passport. I gave it to him, and he ran off with it.” |

That, too, may sound ridiculous, giving a complete stranger your passport, but in fact one of our students did precisely that in ’89. She got to know the American Embassy pretty well in the process of getting a new one.

| — Откуда ты? — От врача. Мне пришлось пройти тест на ВИЧ. — Ты думаешь, что у тебя ВИЧ? — Да нет, просто без теста не выдают визы в Россию. |

“Where are you coming from?” “From the doctor's office. I had to have an HIV test.” “You think you have HIV?” “Oh, no. It's just the you can't get visas to Russia without one.” |

That, too, may sound ridiculous, but all our students have to have HIV tests to get a visa. I think this is part of the tit-for-tat. Up until January of 2010 the US also required HIV tests for people getting visas to enter the country. Now that the requirement has been lifted, it will be interesting to see if Russia lifts it as well.

Же

The word же is an emphatic particle, by which we mean it puts emphasis on the preceding word. My first-year college Russian instructor first suggested translating it into English with the phrase ‘in the world.’ I still like that approach after question words:

| Кто это? | Who is this? Who is that? |

| Кто же это? | Who in the world is this? Who in the world is that? |

| Что это? | What is this? |

| А что же это? | And what in the world is this? |

| Где мои ключи? | Where are my keys? |

| Где же мои ключи? | Where in the world are my keys? |

| Куда ты идёшь? | Where are you going? |

| Куда же ты идёшь? | Where in the world are you going? |

Же has many other uses and translations as well. It's especially worth taking the time to contemplate how it's used in translating the English phrase ‘the same’ in this blog entry.

Куда же ты идёшь?

Куда-куда, на кудыкину гору.

Where the heck are you going?

I'll never tell.

Приглашать/пригласить

The verb pair приглашать/пригласить means ‘to invite.’ Note the с~ш alternation in the perfective:

| Imperfective | Perfective | |

| Infinitive | приглашать | пригласить |

| Past | приглашал приглашала приглашало приглашали |

пригласил пригласила пригласило пригласили |

| Present | приглашаю приглашаешь приглашает приглашаем приглашаете приглашают |

No such thing as perfective present in Russian. |

| Future |

буду приглашать будешь приглашать будет приглашать будем приглашать будете приглашать будут приглашать |

приглашу пригласишь пригласит пригласим пригласите пригласят |

| Imperative | приглашай(те) | пригласи(те) |

The person you invite goes in the accusative case:

| — Кого ты пригласила? — Глеба и Борю. |

“Who did you invite?” “Gleb and Boris.” |

| — Почему ты пригласил Настю? — Потому что я от неё без ума! |

“Why did you invite Anastasiya?” “Because I'm crazy about her!” |

The place you invite someone to appears in a motion phrase, so you often have в/на followed by the accusative case:

| Президента Обаму пригласили в Ирландию. | President Obama was invited to Ireland. |

| Уго Чавеса пригласили на Кубу. | Hugo Chavez was invited to Cuba. |

You can also use к + dative to specify the person one is going to visit, which more often than not is specified with к себе or к нам, and в гости is often included as well:

| Петровы пригласили меня. | The Petrovs invited me. The Petrovs have invited me. |

| Петровы пригласили меня к себе. | The Petrovs invited me to their place. The Petrovs have invited me to their place. |

| Петровы пригласили меня к себе в гости. | The Petrovs invited me to visit them. The Petrovs have invited me to visit them. |

It's possible to get names after к as well:

| Шевчука не пригласили к Медведеву из-за его «подростковости и нонконформизма». (source) | Shevchuk was not invited to see Medvedev because of his childishness and nonconformism. |

| Тимошенко не пригласили к Шустеру по случаю 8 Марта. (source) | Timoshenko was not invited to see Shuster for March 8th.¹ |

| Лучших сварщиков пригласили к губернатору. (source) | The best welders have been invited to see the governer. |

¹ Савик Шустер is the host of «Шустер live», a Ukrainian socio-political talk show. Despite being broadcast on Ukrainian TV, the show is conducted in Russian.

Вы

Most human languages have separate words for you-singular and you-plural. Russian is no exception. The plural you in Russian is вы, which declines like this:

| Pl | |

| Nom | вы |

| Acc | вас |

| Gen | |

| Pre | |

| Dat | вам |

| Ins | вами |

Any time you address more than one person in Russian, you must use the вы form instead of the ты form:

| — Откуда вы? — Мы из Одессы. |

“Where are you from?” “We are from Odessa.” |

| Дорогие студенты, предупреждаю вас, что экзамен будет очень трудным. | Dear students, I must warn you that the exam will be difficult. |

In Russian the вы form is also used to speak politely to a single individual; it's the form you normally use when meeting a stranger or talking to someone who is your superior at work or to someone you don't know very well:

| — Откуда вы? — Я из Одессы. |

“Where are you from?” “I am from Odessa.” |

| Иванов, предупреждаю вас, что экзамен будет очень трудным. | Ivanov, I must warn you that the exam will be difficult. |

Now here is a subtlety. If вы is the subject of a sentence that has a predicate adjective, and if the adjective is a short form adjective, then you must use the plural form; but if it is a long form adjective, you must use the singular with corresponding gender agreement. Thus if I am talking to a woman I may say:

| Short form: Вы очень красивы. Long form: Вы очень красивая. |

You are very pretty. |

If I am talking to a man, I may say:

| Short form: Вы очень красивы. Long form: Вы очень красивый. |

You are very handsome. |

I should note that some of those sentences may sound a bit stilted in Russian. Russian-speakers tend to use predicate adjectives less often than English-speakers, and one needs a bit of experience to figure out when they sound okay and when one should use an alternative constructive. Grammatically, though, all four sentences are correct.

Перец (часть вторая)

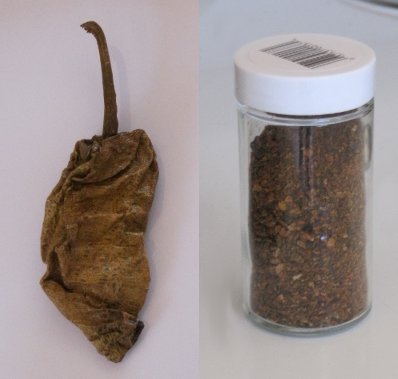

On Monday I depart for Russia. I love spicy food, so usually when I travel I take a bottle of Tabasco Sauce with me. This year, though, I'm taking a jar of ground chipotles with me:

| Чипотле — это копчёный перец «халапеньо» | A chipotle is a smoked jalapeño. |

If that's not an excuse to discuss перец ‘pepper’, I don't know what is. Notice that the word has a fleeting vowel:

| Sg | Pl | |

| Nom | перец | перцы |

| Acc | перец | перцы |

| Gen | перца | перцев |

| Pre | перце | перцах |

| Dat | перцу | перцам |

| Ins | перцем | перцами |

A chipotle is an ugly-looking thing, but the flavor it imparts to food is nigh miraculous. Here on the left you can see one before it's ground. On the right you see the product of grinding six chipotles in the blender.

| Я у себя дома размалываю копчёные перцы в блендере. | I grind smoked peppers at home in a blender. |

| Я всегда жарю молотый копчёный перец на масле перед тем, как сделать яичницу. | I always fry some ground smoked pepper in butter before making scrambled eggs. |

| У меня во рту горит от острого перца. | My mouth is burning from the hot pepper. |

| Я люблю есть пельмени со сметаной и молотым копчёным перцем. Это не традиционно, но вкус такой — обалдеть! | I love to eat pelmeni with sour cream and ground smoked pepper. It's not traditional, but the taste is freaking awesome! |

Although I love spicy food, I have to say there is a limit. Jalapeños and serranos are about as hot as I like it. Habaneros? Can't touch them. The hottest pepper in the world, as far as I know, is the naga jolokia. Check out the youtube videos of children and adults making idiots of themselves eating them.

<< 1 ... 23 24 25 ...26 ...27 28 29 ...30 ...31 32 33 ... 158 >>