Друг друга, друг дружку

The Russian phrase for “each other” is formed by saying the word друг twice in a row. The second друг occurs in a case other than the nominative, i.e. you can find these five forms:

| Nom | - |

| Acc | друг друга |

| Gen | друг друга |

| Pre | друг о друге |

| Dat | друг другу |

| Ins | друг другом |

The case of the second друг depends most often on the verb in question. If the verb requires a direct object, the second друг shows up in the accusative case; if the verb requires a dative object, the second друг shows up in the dative case. Likewise genitive — genitive, and instrumental — instrumental. Here are some examples:

| Мы хорошо знаем друг друга. | We know each other well. |

| Мы с женой часто покупаем друг другу подарки. | My wife and I often buy each other gifts. |

| Американцы и русские раньше боялись друг друга. | Americans and Russians used to be afraid of each other. |

| Несмотря на их взаимную подозрительность, русские и американцы интересовались друг другом. | Despite their mutual suspicion, Russians and Americans were also very interested in each other. |

If the verb requires a prepositional phrase as its complement, then the preposition comes between the two другs:

| Мои сёстры постоянно сплетничают друг о друге. | My sisters constantly gossip about each other. |

| Когда мы были детьми, мы с братом постоянно ссорились друг с другом. | When we were boys, my brother and I constantly argued with each other. |

| Во время дуели противники стреляют друг в друга. | During a duel the contenders shoot at each other. |

| Улитки медленно подползали друг к другу | The snails slowly crawled toward each other. |

Native English speakers, of course, will be tempted to write things like «Мои сёстры постоянно сплетничают о друг друге». And truth to tell, native Russians will say or write something like that, but it is not considered good written style.

Interestingly enough, sometimes the Russians substitute дружка for the second друг. Thus you get:

| Nom | - |

| Acc | друг дружку |

| Gen | друг дружки |

| Pre | друг о дружке |

| Dat | друг дружке |

| Ins | друг дружкой |

That makes the phrase much more informal and conversational. For instance:

| Солистки «ВИА Гры» ненавидят друг дружку лютой ненавистью. (source) | The singers of [the pop group] “VIA Gra” hate each other bitterly. |

I was interested to find the phrase as well in a site devoted to Russian folk magic. Here is a spell people use to help repair a family fracas:

| Жгут ладан на сковороде и обходят с ним дом. |

Burn incense in a frying pan and walk around the house with it. |

| Читают следующее: Ночь с луной, звезда с звездой, я со своей семьёй. |

Read the following: Like the moon and the night, like star with star, so me and my family. |

| Как любит Христос свою мать, | As Christ loves his mother, |

| так чтобы мы все друг дружку любили, | so may we love each other |

| а не грызлись и друг друга не били. |

may we not squabble nor beat each other. |

| Ладан, лад дай, мир и клад. Аминь. |

Incense, give us amity peace and order. Amen. |

You'll notice that жгут, обходят and читают are not command forms but third person plural verbs. In the translation they are rendered as imperatives to make the English flow better.

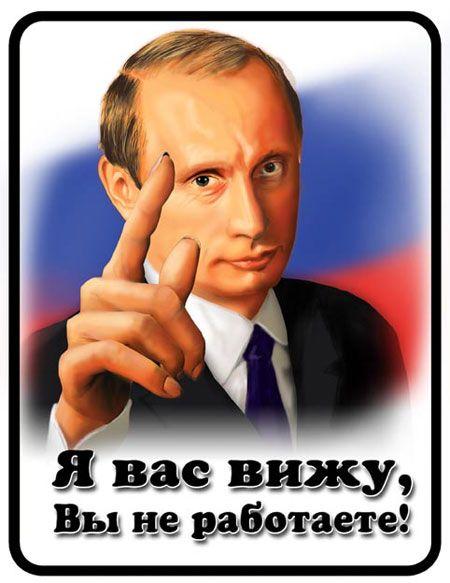

Видеть/увидеть

The verb видеть/увидеть means “to see.”

| to see | ||

| Imperfective | Perfective | |

| Infinitive | видеть | увидеть |

| Past | видел видела видело видели |

увидел увидела увидело увидели |

| Present | вижу видишь видит видим видите видят |

No such thing as perfective present in Russian. |

| Future |

буду видеть будешь видеть будет видеть будем видеть будете видеть будут видеть |

увижу увидишь увидит увидим увидите увидят |

| Imperative | Generally not used | |

While the imperfective is almost always translated “to see,” the perfective can often be translated “to spot, to catch sight of”:

| Каждый день я вижу туристов перед Оружейной палатой. | Every day I see tourists in front of the Kremlin Armory. |

| Я не вижу никакой причины, почему тебе пришлось обидеть мою маму. | I don't see any reason why you had to offend my mother. |

| Если увидишь ГАИ, то уменьши скорость, а то тебя оштрафуют. | If you spot traffic cops, then slow down; otherwise you'll be fined. |

| — Я вчера увидел твою бывшую подругу в кино. Она была с новым парнем. Она казалась очень счастливой. — Такие новости меня не интересуют. |

“I spotted your old girlfriend yesterday at the movies. She was with a new guy. She seemed really happy.” “I really don't care.” |

Наушники

The Russian word наушники is translated as headphones. Just like in English, this term is used to refer to all types of headphones when the description is added in front: беспроводные наушники (wireless headphones), вставные наушники (earbuds), стерео наушники (stereo headphones), диджейские наушники (DJ headphones) and etc.

The word наушник (headphone) is a combination of the preposition на (on), the word уши (ears), and a suffix -ник that turns the combination into a noun.

| Sg | Pl | |

| Nom | наушник | наушники |

| Acc | ||

| Gen | наушника | наушников |

| Pre | наушнике | наушниках |

| Dat | наушнику | наушникам |

| Ins | наушником | наушниками |

Here are some example sentences:

| Каждый раз, когда я покупаю новые наушники, у меня их забирает мой старший брат. | Every time I buy new headphones, my older brother takes them away from me. |

| Сколько этим наушникам лет? По-моему, ты иx носил ещё в восьмидесятых. | How old are these headphones? I think you were wearing them back in the eighties. |

| Правый наушник почему-то опять сломался, а левый работает как новенький. | The right headphone broke for some reason, while the left one works as if it’s new. |

| Маше не нравится ходить в больших наушниках, потому что ей кажется, что она в них смешно выглядит. | Masha doesn’t like to walk around in large headphones because she thinks that she looks funny in them. |

Picture from fareastgizmos.com

| — Какие у тебя крутые наушники. | “What cool headphones you’ve got.” |

| — Спасибо, это новые звуконепроницаемые наушники Bose. Я на них просадил почти половину своей зарплаты, но нисколько об этом не сожалею. | “Thanks, these are the new Bose noise-canceling headphones. I spent almost half of my salary on them but don’t regret it at all.” |

| — Да, звук — это главная вещь в жизни. Можно, пожалуйста, послушать? | “Yes, sound is the most important thing in life. Can I please listen to them?” |

| — Вот, надевай. | “Here, put them on.” |

| — Какой потрясающий звук, но к тридцати годам будешь глухим. | “What an amazing sound, but you’ll be deaf before you’re thirty.” |

| — Ничего страшного, к тому времени доктора что-нибудь придумают. Я уже и так плохо слышу.” | “No big deal. By that time the doctors will think of something. I already have bad hearing anyway.” |

Хрипнуть/охрипнуть

The other day I was talking with my buddy Юрий when my brain rаn up against a linguistic wall: I didn't know how to say “I lost my voice” in Russian. Of course, a good language student never lets the lack of vocabulary stop him. He just improvises with words he does know. So I said “у меня исчез голос”, literally “at me the voice disappeared.” That made the communicative point and the conversation continued, but I was irked that I didn't really know the way a Russian would normally say it. So I started asking about that concept and here's what I came up with.

First of all, there is the verb хрипнуть/охрипнуть, which covers two concepts in English: “to have/get a hoarse voice” and “to lose one's voice.” The verb is conjugated like this:

| Imperfective | Perfective | |

| Infinitive | хрипнуть | охрипнуть |

| Past | хрип хрипла хрипло хрипли |

охрип охрипла охрипло охрипли |

| Present | хрипну хрипнешь хрипнет хрипнем хрипнете хрипнут |

No such thing as perfective present in Russian. |

| Future |

буду хрипнуть будешь хрипнуть будет хрипнуть будем хрипнуть будете хрипнуть будут хрипнуть |

охрипну охрипнешь охрипнет охрипнем охрипнете охрипнут |

| Imperative | хрипни(те) | охрипни(те) |

Since this verb covers the meaning of two different phrases, sometimes it has two possible translations:

| Весной она всегда хрипнет. | In springtime her voice always gets hoarse. or In springtime she always loses her voice. |

That means that if you are translating something from Russian to English, you might have to pay close attention to context to see whether completely losing the voice or becoming hoarse is the point. Of course, there can't be that many contexts where it's important to distinguish between simply becoming hoarse (partially losing one's voice) and completely losing one's voice, so maybe the issue is mostly moot.

Here's another example:

| Вчера моя жена так долго ругала меня, что совсем охрипла, и сегодня в доме господствует блаженная тишина. | Yesterday my wife chewed me out for so long that she completely lost her voice, and today blessed silence reigns in our home. |

There are a couple other phrases that mean the same thing. We can use the verb оседать/осесть “to sink” or терять/потерять “to lose.” For instance:

| На прошлой неделе Витя так упорно болел за Спартак, что у него осел голос. | Last week Victor cheered for Spartak so intensely that he lost his voice. |

| — В начале учебного года я всегда теряю голос. Школьники — это пакостные гады, которые заражают всех окружающих. | “At the beginning of the school year I always lose my voice. Schoolchildren are nasty vermin that infect everybody around them.” |

| — Погоди! Я думал, что ты любишь работать учительницей. | “Wait a minute! I thought you loved working as a school teacher.” |

| — Люблю, но это не значит, что дети не пакостные гады. | “I do. But that doesn't mean that children aren't nasty vermin.” |

| Бабушка всегда хрипнет при влажной погоде. | Grandma always gets hoarse/loses her voice in humid weather. |

Тарелка

The word тарелка is translated as plate. For the most part, it is a kitchen term, but can also be used to describe a UFO saucer (летающая тарелка), a satellite dish (спутниковая тарелка), or the percussion instrument cymbal.

| Sg | Pl | |

| Nom | тарелка | тарелки |

| Acc | тарелку | |

| Gen | тарелки | тарелок |

| Pre | тарелке | тарелках |

| Dat | тарелкам | |

| Ins | тарелкой | тарелками |

Here are some sample sentences:

| Папа разбил три тарелки, пока готовил обед. | Dad broke three plates while cooking dinner. |

| Фарфоровая тарелка ручной работы может дорого стоить в их магазине. | A hand made porcelain plate can cost a lot of money at their store. |

| Барабанщик, как же ты будешь сегодня играть без тарелок? Иди скорей и попроси их у кого-нибудь занять на пару песен. | Drummer, how are you going to play without the cymbals? Hurry up and ask someone to let you borrow them for a couple of songs. |

| Oдин раз кто-то мне просто так вылил на голову тарелку борща. | One time someone poured a plate of borsch on my head for no apparent reason. |

The translation of that last sentence sounds very odd to the American ear: after all, no one would ever serve you soup on a plate because a plate is mostly flat and the soup would run off! But in Russian тарелка includes dishes that are deep enough to be called bowls in American English. You'll still find “plate of soup” in older English translations of Russian literature, but if the target audience of your translation is American, then the better translation is “bowl.” Take a look:

Image taken from vkusnosti.com

Image taken from vkusnosti.comHere's a short, connected dialog that shows you not only the word тарелка, but also has some good vocabulary you'll encounter generally while shoppping.

| — Простите, девушка, почём вот эти тарелки? | “Excuse me, Miss, how much are these plates?” |

| — По шестьсот рублей. Hо могу сделать вам скидку, если купите шесть или больше. | “Six hundred rubles each. But I can give you a discount if you buy six or more.” |

| — Cколько? | “How much?” |

| — Hу, например пятьсот двадцать за каждую. Тарелки из Санкт-Петербурга, так что дешевле вы нигде не найдёте. | “Well, for example five hundred and twenty per each. The plates are from St. Petersburg so you won’t find them cheaper anywhere else. |

| — Ладно, возьму! | “Ok, I’ll take them!” |

| — Oтлично, с вас пожалуйста три тысячи пятьсот рублей. | “Great, it’s three thousand five hundred rubles please.” |

| — Вот. | “Here.” |

| — Большое спасибо, приходите ещё. | “Thank you very much, come again.” |

<< 1 ... 95 96 97 ...98 ...99 100 101 ...102 ...103 104 105 ... 158 >>