Categories: "Grammar"

Приносить/принести

The verb pair приносить/принести is usually translated as ‘to bring.’ It conjugates like this:

| Imperfective | Perfective | |

| Infinitive | приносить | принести |

| Past | приносил приносила приносило приносили |

принёс принесла принесло принесли |

| Present | приношу приносишь приносит приносим приносите приносят |

No such thing as perfective present in Russian. |

| Future |

буду приносить будешь приносить будет приносить будем приносить будете приносить будут приносить |

принесу принесёшь принесёт принесём принесёте принесут |

| Imperative | приноси(те) | принеси(те) |

The bringer appears in the nominative case, and the thing brought appears in the accusative:

| — Кто принёс эту картинку? — Картинку принесла Ксюша. |

“Who brought this painting?” “The painting was brought by Kseniya.” |

| Вань, принеси ножницы, пожалуйста. | Ivan, bring the scissors, please. |

When you bring something to a person, the person appears in the dative case.

| По пятницам папа всегда приносит маме цветы. | On Fridays Dad always brings Mom flowers. |

When you bring something to a place, you usually use в/на + accusative:

| Бывшая секретарша всегда приносила пирожные на работу. | The previous secretary always brought pastries to work. |

| Если принесёшь мобильник в ресторан, я покажу тебе, как скачать MP3 [эм-пэ-три]. | If you bring your cellphone to the restaurant, I'll show you how to download MP3s. |

For English speakers we must keep in mind a couple caveats about this verb pair. First of fall, since the verb implies taking something somewhere in your own arms, you can't use it to say you brought a person to a place unless the person you bring is a baby. Secondly, if you bring something from another city or country, you should use the verb привозить/привезти, which implies motion by vehicle.

Приезжать/приехать

The verb pair приезжать/приехать is usually translated as “to arrive, come,” and it implies movement by vehicle. It conjugates like this:

| Imperfective | Perfective | |

| Infinitive | приезжать | приехать |

| Past | приезжал приезжала приезжало приезжали |

приехал приехала приехало приехали |

| Present | приезжаю приезжаешь приезжает приезжаем приезжаете приезжают |

No such thing as perfective present in Russian. |

| Future |

буду приезжать будешь приезжать будет приезжать будем приезжать будете приезжать будут приезжать |

приеду приедешь приедет приедем приедете приедут |

| Imperative | приезжай(те) | приезжай(те) |

In English we often use the preposition “at” with the verb “arrive,” so we have to bear in mind that for Russians arrival is a motion; that is, you complement the verb with either в/на + accusative or with к + dative:

| Профессор приехал в Москву в восемь часов утра. | The professor arrived in Moscow at eight o'clock. |

| Юля всегда приезжала на вокзал поздно. | Julie always arrived at the train station late. |

| Когда ты приедешь к нам? | When will you come to our place? |

One point of translation: in English if you see a vehicle approaching, you may say “Here comes the bus/train/taxi.” In Russian you will never use приезжать/приехать in that context. Instead you most commonly use the verb идти.

| Вот идёт поезд. | Here comes the train. |

| Посмотри, вот идёт такси. | Look, here comes the taxi. |

Рисовать/нарисовать

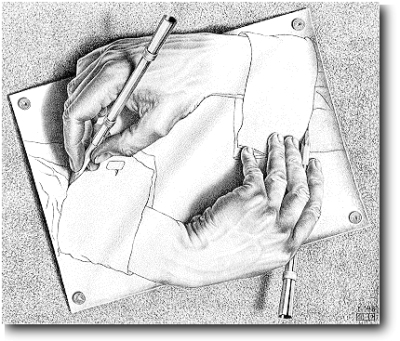

M.C. Escher-one of my favorites

Today's word of the day is the verb рисовать. This means to draw. As in a picture, not а lottery. I grew up loving to draw and doodle. So much, that I was often in trouble for drawing during all my classes.

| Imperfective | Perfective | |

| Infinitive | рисовать | нарисовать |

| Past | рисовал рисовала рисовало рисовали |

нарисовал нарисовала нарисовало нарисовали |

| Present | рисую рисуешь рисует рисуем рисуете рисуют |

No such thing as perfective present in Russian. |

| Future |

буду рисовать будешь рисовать будет рисовать будем рисовать будете рисовать будут рисовать |

нарисую нарисуешь нарисует нарисуем нарисуете нарисуют |

| Imperative | рисуй(те) | нарисуй(те) |

Here are some examples using our word:

Он рисует красивый цветок.

He is drawing a beautiful flower.

Я учусь рисовать.

I am learning to draw.

Я собираюсь наказать всех моих детей. Они рисовали на стене!

I am getting ready to punish all my kids. They drew all over the wall!

Катя, пожалуйста, нарисуй мне что-нибудь.

Katya, please draw me something.

Жаль (часть первая)

Sometimes in life you're just bummed out about something, and one of the words that expresses that idea in Russian is жаль. Жаль expresses an idea of sadness or regret or irritation; it can form an entire sentence unto itself:

| Жаль. | That's a shame. or That's a bummer. or |

If want to add the “what a” idea to it, you use как:

| Как жаль. | What a shame. or What a bummer. or |

Very often жаль is followed by a clause beginning with что:

- Жаль, что она не пришла.

- It's a shame that she didn't come. or

It's a pity that she didn't come. - Жаль, что ты так мало зарабатываешь.

- It's a pity that you earn so little. or

It's a shame that you earn so little.

If you want to incorporate the idea of who is experiencing the pity, then the person goes into the dative case. Once the person is added, though, it flows best if you don't use the words pity and shame in Engish translation. Instead other versions sound better:

- Мне жаль, что она не пришла.

- I'm disappointed that she didn't come. or

I'm sad that she didn't come. or

I'm bummed that she didn't come. or

I feel bad that she didn't come. - Лене жаль, что ты так мало зарабатываешь.

- Lena's sad that you earn so little. or

Lena's disappointed that you earn so little. or

Lena's bummed that you earn so little. or

Lena feels bad that you earn so little.

To put the жаль phrase into the past or future tense, use было and будет respectively:

| Мне было жаль, что она не пришла. | I was disappointed that she didn't come. |

| Мне будет жаль, если она не придёт. | I will be disappointed if she doesn't come. |

| Лене было жаль, что она не смогла встретиться с тобой. | Lena was disappointed that she couldn't get together with you. |

| Лене будет жаль, если ты ей не позвонишь. | Lena will be disappointed if you don't call her. |

Три

The most common word for three in Russian is три. If три occurs in the nominative case, then it is followed by the genitive singular form of the noun:

| три сына | three sons |

| три дочери | three daughters |

| три письма | three letters |

However, if you put an adjective between the number and the noun, you don't use the genitive singular. So what form do you use? Well, that depends...

If you are dealing with masculine or neuter nouns, then you have to use an adjectival form that copies the genitive plural:

| три красивых сына | three handsome sons |

| три длинных письма | three long letters |

If you are dealing with feminine nouns, it is usually best to use an adjectival form that copies the nominative plural:

| три красивые дочери | three pretty daughters |

Here are some sample sentences:

| На крыше загорали три иностранных туриста. | There were three foreign tourists sunbathing on the roof. |

| У инопланетянина были три жёлтые головы и два красных хвоста. | The alien had three yellow heads and two red tails. |

| Три старых профессора играли в шахматы в парке. | Three old professors were playing chess in the park. |

| У меня три японских телевизора. | I have three Japanese televisions. |

¹ You will sometimes also encounter три красивых дочери, аlthough красивые is better style these days.

<< 1 ... 12 13 14 ...15 ...16 17 18 ...19 ...20 21 22 ... 49 >>