Categories: "Grammar"

Как (часть вторая)

Every Russian 101 student knows that the word как can mean ‘how.’ There are other contexts, though, where как is best left untranslated. This is particularly true after the verbs видеть ‘to see’, заметить ‘to notice’, наблюдать ‘to observe’, следить ‘to observe’, слушать ‘to listen’, слышать ‘to hear’ and смотреть ‘to watch’.

| Мы слушали, как пели птицы. | We listened to the birds singing. |

In this kind of sentence the word как has no ‘how’ meaning at all; it simply marks the beginning of a new clause. In other words, this sentence does NOT mean “We listened to how the birds were singing.” The sentence means we listened to the event itself, not that we were trying to discern the manner in which they sang. Here are some other simple examples:

| Ты слышал, как соседка ругала сына? | Did you hear our neighboring scolding her son? |

| Мама смотрела, как Наташка каталась по двору на скейтборде? | Mom watched Natalya ride around the courtyard on the skateboard. |

You will notice that all three of the previous sample sentences had an imperfective past tense verb in the subordinate clause. If the action of the subordinate clause takes place at the same time as the action of the main clause, then you can have a present tense verb in the subordinate clause without changing the meaning, e.g.:

| Мы слушали, как поют птицы. | We listened to the birds singing. |

| Ты слышал, как соседка ругает сына? | Did you hear our neighboring scolding her son? |

| Мама смотрела, как Наташка катается по двору на скейтборде? | Mom watched Natalya ride around the courtyard on the skateboard. |

Here are some more complex sentences that use the construction:

| Державин слушал, как молодой Пушкин читал свои стихи. | Derzhavin listened to the young Pushkin reciting his poetry. |

| Дети видели, как разбился самолет. (source) | The children saw the plane break into pieces. |

| Все думали, что аэропорт закроют, но было слышно, как садятся самолеты. (same source) | Everyone thought that they would close the airport, but one could hear the planes landing. |

| Вера тихо лежала в постели и слушала, как пели птицы. | Vera quietly lay in bed and listened to the birds singing. |

| Милиционеры наблюдали, как подозреваемый вошёл в банк. | The policemen observed the suspect enter the bank. |

Ли (часть первая)

A reader recently asked me to address the word ли. That's an excellent topic for a beginning Russian blog, but before we talk about ли, we should get a little background information. When Russians ask yes-no questions, they usually use the same words as an ordinary statement, but they change the intonation. For instance, a statement “Boris speaks English” comes out like this, where the blue line indicates the approximate intonation pattern:

That pattern is known as “intonation construction 1” in Russian pegadogical circles. To turn that into the question “Does Boris speak English?”, we rephrase it using “intonation construction 3”:

It's a pain in the rear to design special graphics to outline every sentence in which you wish to indicate intonation, so we often use a rather more compact way of indicating intonation with numbers. The syllable on which the most drastic shift of tone takes places is called the “intonation center.” Once you have indicated where the intonation center is, everything else about the tone pattern is predictable, so we simply indicate the intonation center by writing the number above the vowel where that dramatic shift happens. For instance, the statement “Boris speaks English” is represented like this:

1 Борис говорит по-английски.

The question “Does Boris speak English?” is represented like this:

3 Борис говорит по-английски?

Theoretically you can put intonation construction three on any part of the sentence that bears the logical focus of the question. If the question is general, then you usually end up putting the intonation on the verb, thus

3 Мама хочет пойти домой?

means “Does Mom want to go home?”, whereas

3 Мама хочет пойти домой?

means something like “Mom wants to go home?”, i.e., the focus is on whether she wants to go home as opposed to some other place. Contrast that with

3 Мама хочет пойти домой?

which means something like “Is it Mom who wants to go home?”, i.e. the focus is on whether it is Mom who wants to go home, as opposed to Grandma or someone else.

Bearing that in mind, there is another way of asking yes-no questions in Russian, and that is by using ли, which is a postclitic particle. By particle we mean a word that never changes its endings. By clitic we mean that it is pronounced as part of a word that it is next to. By post- we mean that it is pronounced as part of the word it appears after. As a postclitic it will never be the first item in a sentence; it must be the second item. Thus if we want to rephrase “Does Boris speak English?” using ли, it would come out like this:

3 Говорит ли Борис по-английски?

The three other questions we looked at above would be rephrased like this:

3 Хочет ли мама пойти домой? 3 Домой ли мама хочет пойти? 3 Мама ли хочет пойти домой?

Yes-no questions without ли are perfectly normal in spoken Russian. When you add ли, it raises the stylistic level a bit, making it more formal or more polite.

In all our examples here, there is only one word before ли. It's possible to have more than one word in front of it, and in fact in some contexts it's very common. We'll discuss those in the next article on ли.

Note: some of the examples in this blog entry may seem a bit stilted. It's actually rather difficult to come up with long yes-no questions that comfortably illustrate the different possible focus points of intonation or ли without sounding stilted. The important point to remember here is that theoretically ли can place its focus on any phrase that immediately proceeds it. Despite their awkwardness, all theses sentences are perfectly grammatical Russian, and it would be possible for a Russian to say them given a suitable context preceding them.

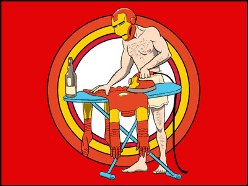

Гладить/выгладить

Nobody likes chores. And everyone has that one chore they despise above all others. I would rather be tied to a chair and forced to watch reruns of “Barney and Friends” than iron clothing. Thank goodness I live in the century of electric dryers. The Russian word гладить means to iron or press.

| Imperfective | Perfective | |

| Infinitive | гладить | выгладить |

| Past | гладил гладила гладило гладили |

выгладил выгладила выгладило выгладили |

| Present | глажу гладишь гладит гладим гладите гладят |

No such thing as perfective present in Russian. |

| Future |

буду гладить будешь гладить будет гладить будем гладить будете гладить будут гладить |

выглажу выгладишь выгладит выгладим выгладите выгладят |

| Imperative | гладь(те) | выгладь(те) |

Я ненавижу гладить одежду.

I hate to iron clothes.

Что вы гладите?

What are you ironing?

Я глажу мою юбку.

I am ironing my skirt.

Железный человек гладил рабочую униформу.

Iron Man was ironing his work uniform.

http://www.tshirtbordello.com/Ironing-Man-T-Shirt

* Although гладить translates to iron it has nothing to do with the metal, iron. For that you would use железо.

Как (часть первая)

The Russian word for ‘how’ is как. When you start studying Russian, you first encounter it in “How are you?” phrases:

| Как дела? | How are things going? |

| Как живёшь? | How are you? |

Since the word asks about the manner in which something is done, we call it an adverb. Since it poses a question we call it an interrogative adverb. In the following sentences the word is an interrogative adverb. In English we often use the pronoun ‘you’ or ‘I’ or (if you are really pedantic) ‘one’ in sentences that ask how to do something. Similar sentences in Russian often ask usе an infinitive construction:

| Как доехать до университета? | How can I get to the university? |

| Как лучше добраться до Москвы? На поезде или на самолёте? | How is it best for one to get to Moscow? By train or by plane? |

| Как приготовить борщ? | How do you make borshch? |

| — Как можно избежать штрафов за превышение скорости, зафиксированное фото радарами? — Приобретите себе радарную систему с выведенной из эксплуатации подводной лодки и установите её в своей машине. Её сигнал пересилит сигнал радаров городского движения и вы будете кататься по всему городу, не получая никаких штрафов. |

“How can I avoid photo radar fines?” “Get yourself a radar system from a decommissioned submarine and install it in your car. The signal will overwhelm city traffic radar, and you will be able to ride all over town without any fines whatsoever.” |

А

Back in the seventies American television had a little spasm in which it thought that blurbs between TV shows on Saturday mornings should be educational. There was “Bicentennial Rock” as 1976 approached, and there was “Multiplication Rock” and even “Grammar Rock.” Grammar Rock rocked! And of all the songs none was better than “Conjunction Junction”:

♪ Conjunction Junction, what's your function? ♫

♫ “Hookin' up words and phrases and clauses.” ♪

Of course, that was before “hooking up” acquired a different meaning... If you haven't ever watched the video, do it immediately or end up a grammatical imbecile.

In Russian there are three conjunctions that give us Americans fits, and they are но, а and и. The reason they give us fits is that in American English we mostly use two conjunctions in their stead, ‘and’ and ‘but,’ but they don't line up quite the way we Americans might expect. Today we will talk about «а». The conjuction «а» can be translated as ‘but,’ ‘and’ or ‘whereas.’ Probably the first rule of thumb for us AmE-speаkers is that if you are contrasting subjects in a sentence, you want to use «а» not «и»:

| Мама пошла на рынок, а папа пошёл в аптеку. | Mom went to the market, and Dad went to the pharmacy. |

| Мой брат работает в больнице, а моя сестра работает в бизнесе. | My brother works at a hospital, and my sister works in a business. |

| Саша любит сладкое, а Дима любит острое. | Sasha likes sweet food, and Dima likes spicy food. |

| В отпуск Люба летала на Гавайи, а Ира ездила в Норильск. | Lyuba flew to Hawaii for vacation, and Ira went to Norilsk. |

I don't mean to say that the only time you use «а» is when subjects are contrasted, but this is a good idea to start with.

<< 1 ... 10 11 12 ...13 ...14 15 16 ...17 ...18 19 20 ... 49 >>