Что (часть первая)

The Russian word for ‘what’ is что. Although it is written with the letter ч, the nominative/accusative form of the word is most commonly pronounced [што]; in the other cases we do pronounce ч as ч. It occurs in all six cases:

| Nom | что |

| Acc | что |

| Gen | чего |

| Pre | чём |

| Dat | чему |

| Ins | чем |

Notice that the only difference between the prepositional and instrumental forms is the двоеточие “double dots” over the prepositional form.¹ Remember that the Russians usually do not usually write the double dots, so context will have to tell you how to pronounce those forms. Some sample sentences:

| — Что ты купил? — Овощи и чай. |

“What did you buy?” “Vegetables and tea.” |

| Что там лежит на столе? | What's that lying on the table? |

Somewhere in school every American is taught the rule “never end a sentence with a preposition.” For English it's an assinine rule that has no reasonable justification in the living language.² However, for Russian the rule is real and alive. It's not an artificial rule, as in English, but rather a subconscious part of the living language: no Russian will ever end a sentence with a preposition, not even accidentally. So whenever you are translating a question from English to Russian, and the question ends with a preposition, you need to move that preposition to before its object and then translate. Thus:

Other examples:

| — В чём живут пчёлы? — В ульях. |

“What do bees live in?” “In hives.” |

| — Из чего сделан тот сарай? — Из досок дуба. |

“What's that shed made of?” “It's made of oak boards.” |

| — Чем ты написал сочениние? — Карандашом. — Тогда надо переписать ручкой, а то не примут. |

“What did you write your composition with?” “With a pencil.” “Then you'll have to rewrite it with a pen, otherwise they won't accept it.” |

| — К чему стремятся глобалисты? — К унифицированию всего человечества. |

“What are the Globalists striving for?” “For the unification of all humanity.” |

| — Мы встретились перед памятником Пушкину. — Перед чем? — Перед памятником Пушкину. |

“We met in front of Pushkin's monument.” “In front of what?” “Pushkin's monument.” |

Notice in the last example we can leave the preposition out of the response in English, but in Russian you must retain the preposition to justify the case of памятник.

¹ The double dots symbol is often called a diaeresis or an umlaut. The former is theoretically used to indicate that a vowel is pronounced as a complete vowel (not a diphthong) when preceded by another vowel with which it might blend. The latter is theoretically used to indicate that vowel is fronted. Since neither of those instances prevails in the е/ё distinction, “double dots” is a sensible name for the symbol.

² Of course, one can't mention this rule of English without mentioning Winston Churchill's famous definition: “A preposition is a word you can't end a sentence with.” I actually doubt that Churchill said it, but it's too fun not to mention.

Шпилька

Heaven knows why, but the other day I took an online Russian test and was dismayed to discover that I didn't know the Russian word for hairpin. You may wonder why I was dismayed. After all, why does a foreign man need to know that word when he is never going to wear one in his hair? But the way I figure it, some day I might be thrown into a Russian prison and have to macgyver my way out of there. Who knows what tools I might have to use in the process? So “hairpin” is a perfectly sensible word for me to know. By the way, it turns out to be шпилька, and the genitive plural is шпилек. Sample sentences:

| Мои волосы сегодня просто не хотели порядочно лежать. Пришлось воспользоваться шпильками. | My hair just didn't want to behave this morning. I had to use bobby pins. |

| В прошлом году меня бросили в тюрьму в Крыму. Я открыл замок камеры шпилькой и прятался три дня в гнилом болоте, пока за мной не прилетел вертолёт, который меня доставил в Женеву. | Last year I was thrown into a prison in the Crimea. I opened the lock of my cell with a hairpin and hid for three days in a putrid swamp until a helicopter flew in to retrieve me and return me to Geneva. |

Types of шпильки

Шпилька actually has a dozen other meanings as well. For instance, it is sometimes used to mean cotter pins, which is not too surprising considering their shape, as well as other cylindrical items that hold metalwork together. It also means stiletto in the sense of a tall thin heel on a high-heeled show. From that it's not surprising that a girl-band took on the name Шпильки “The Stilettoes.” And it can also be used to mean a jibe/dig/snide comment:

| — Как я рада тебя видеть, доченька! Хотя твои волосы вчера шли тебе гораздо лучше, чем сегодня. — Мама, ты всегда хочешь везде шпильки вставить. |

“It's so good to see you, my darling daughter! Although your hair yesterday suited you a lot better than today.” “Mama, why do you always have to say mean things like that?” |

Бежать

Бежать is the determinate (unidirectional) form of the verb бегать “to run.” It is one of the four most irregular verb stems in the Russian language:

| to run | |

| Imperfective | |

| Infinitive | бежать |

| Past | бежал бежала бежало бежали |

| Present | бегу бежишь бежит бежим бежите бегут |

| Future |

буду бежать будешь бежать будет бежать будем бежать будете бежать будут бежать |

| Imperative | беги(те) |

Бежать is more specialized than бегать in that it usually talks about motion in progress at a particular time:

| — Сынок, почему ты бежишь? — Борька сказал, что изобьёт меня! — Подойди к папе. Я тебя защищу. |

“Son, why are you running away?” “Boris said he was going to beat me up.” “Come to Daddy. I'll protect you.” |

| Когда я увидел Таню, она бежала через двор. | When I spotted Tanya, she was running across the courtyard. |

Although the verb does mean “to run,” it's actually used in conversation more often to mean “to take a quick trip” or “to be moving quickly” instead of literally running. The same is true for the English verb “to run” as well, of course.

| — Где мама? — Она бежит в магазин. |

“Where is Mom?” “She is taking a quick trip to the store.” |

| Как быстро бежит время! | How quickly time flies! |

The verb is also used in the sense of “to precede prematurely”:

| Русская зима бежит впереди прогноза. | The Russian winter is running ahead of forecast. |

| Паника бежит впереди фактов. (source) | Panic is setting in before the facts. |

And of course the verb is also used in the sense of “to flee”. Although in English the thing you flee from can be a direct object (“We fled Cuba in 1965”) or the object of the preposition ‘from’ (“We fled from Cuba in 1965”), in Russian the thing you flee from cannot be a direct object; it must be the object of the prepositions из/с/от followed by the genitive case:

| Население бежит с Дальнего Востока. (source) | The population is fleeing from the Far East. |

| Капитал бежит из доллара в золото. (source) | Investors are abandoning dollars for gold. (Lit., Capital is running from the dollar to gold. |

| Жена Лужкова бежит с рынка недвижимости Москвы. (source) | Luzhkov's wife is abandoning Moscow's real estate market. |

| Олигарх мобильной телефонии бежит из России. (source) | Mobile phone oligarch flees Russia. (newspaper headline) |

Гриб

The Russian word for mushroom is гриб, a perfectly regular end-stressed noun:

| Sg | Pl | |

| Nom | гриб | грибы |

| Acc | гриб | грибы |

| Gen | гриба | грибов |

| Pre | грибе | грибах |

| Dat | грибу | грибам |

| Ins | грибом | грибами |

There is a huge cultural difference between Russians and Americans in regards to mushrooms. An American looks at a mushroom in the forest and thinks, “Careful! It might be poisonous!” A Russian looks at a mushroom in the forest and thinks, “My little forest friend! I shall pickle you in oil and spices and consume you with friends in the company of vodka and bliny!”

I never used to eat mushrooms. After all, why would a sane human being deliberately put a fungus that grows in the dirt into his mouth? But then I was served home-preserved mushrooms in Russia. Heaven! The Russians know how to spice, bake, can, wrap, and fry mushrooms better than anyone else on the planet. Now it's a rare day that I don't eat mushrooms, or at least do a little interpretive dance in honor of mushrooms after my morning shower.

| В России растёт свыше двухсот видов съедобных грибов. | More than two hundred varieties of edible mushrooms grow in Russia. |

| Вчера в ресторане нам подали блюдо из грибов с сыром. | Yesterday at the restaurant we were served a dish made of mushrooms and cheese. |

| Под грибом отдыхала улитка. | A snail rested beneath the mushroom. |

| — Какой гриб любят русские больше всего? — Наверно, белый гриб. |

“What mushroom do the Russians like best of all.” “Probably porcini.” |

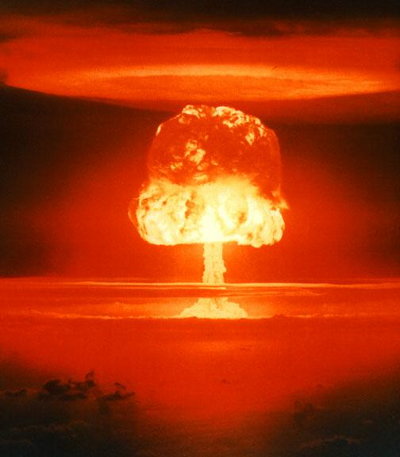

In English everbody knows the phrase “mushroom cloud.” The Russian equivalent is «ядерный гриб» “nuclear mushroom.” That's not particularly surprising. What would surprise an English speaker is that the phrase is used in Russian phrases that mean “really ugly”:

| Лайл Ловетт отличный музыкант, но он страшен как ядерный гриб! | Lyle Lovett is a great musician, but he's as ugly as a mushroom cloud! |

Бегать

Бегать is the most generic word in Russian that means “to run.”

| to run | |

| Imperfective | |

| Infinitive | бегать |

| Past | бегал бегала бегало бегали |

| Present | бегаю бегаешь бегает бегаем бегаете бегают |

| Future |

буду бегать будешь бегать будет бегать будем бегать будете бегать будут бегать |

| Imperative | бегай(те) |

Running… nowadays in the lazy West we often run in order to lose weight. That actually makes sense:

| Бегай каждый день, не ешь хлебных изделий, и обязательно похудеешь. | Go running every day. Don't eat bread or pastry, and you'll lose weight for sure. |

| В 1996-ом я каждое утро бегал, и я отлично чувствовал себя. | In 1996 I ran every morning, and I felt great. |

| Если ты будешь каждое утро бегать, я с удовольствием буду бегать с тобою. | If you are going to run every morning, I'll be happy to join you. |

It's not usual for a person to regularly run from one place to another, but in such atypical circumstances it is possible to conceive of someone doing such a thing:

| Так как Федя готовился к Олимпиаде, он каждый день бегал на работу. | Since Fyodor was getting ready for the Olympics, everyday he ran to work [and back]. |

The verb is also used to describe the motion of someone running around a place with no set goal or direction, e.g. walking around a neighborhood for pleasure:

| Каждый день я бегаю по району не потому, что так рекомендуют врачи, а потому, что таким образом мне становится лучше на душе. | I go running around the neighborhood every morning not because doctors tell us to, but because I feel better that way. |

Last but not least, the verb is used to indicate a single round-trip in the past. It's not typical in this usage, but still grammatically possible:

| Папа бегал в аптеку. | Dad ran to the pharmacy (and then came back). |

<< 1 ... 79 80 81 ...82 ...83 84 85 ...86 ...87 88 89 ... 158 >>