Пока не (союз)

Yesterday we discussed one of the uses of пока in sentences where it means “while.” Sometimes you may encounter a clause that contains both пока and the negative particle не. The first time you see such a thing, you might produce a first-guess translation like this:

| Original | First-guess translation |

| Таня спала, пока не зазвонил будильник. | Tanya slept while the alarm clock didn't start ringing. |

What the devil? Let's see. If she slept while something didn't happen, that means she stopped sleeping when it did happen... in other words, she slept until the alarmclock started rining! That's right: often the proper translation for пока in combination with не is “until”:

| Original | Proper translation |

| Таня спала, пока не зазвонил будильник. | Tanya slept until the alarm clock started ringing. |

This use of «пока…не» to mean “until” can happen in any tense: past, present, or future. The clause in which «пока…не» occurs is called a subjoined clause. For the most part you find the perfective past or perfective future in subjoined пока clauses:

| Мой дядя жил в Одессе, пока он не закончил учёбу. | My uncle lived in Odessa until he finished his studies. |

| Тётя стояла на балконе и курила, пока не пошёл дождик. | My aunt stood on the balcony and smoked until it started to sprinkle. |

| Не уходите, пока я не вернусь. | Don't leave until I get back. |

| Не включай телевизор, пока не напишешь домашнее задание, а то тебе будет плохо. | Don't turn on the TV until you finish doing your homework, or else you're in for it. |

It is also possible for an imperfective verb to appear in the “until” clause if you have to habitually wait for it:

| Дети каждый день ждали у двери, пока не приходил почтальон. | Every day the children waited at the door until the postman came. |

| Каждый вечер после работы мы с Сашей сидим на остановке и болтаем, пока не подходит автобус. | Every evening after work Sasha and I sit at the bus stop and chat until the bus comes. |

Notice that in the first example, both clauses had an imperfective past tense; in the second — an imperfective present tense. It would be logical to assume that you could also put together a sentence like this with both clauses in the imperfective future. In other words something like:

| Theoretically ok sentence | Intended meaning |

| Не забывай, что в следующем месяце днём не будет воды. Нельзя будет нормально купаться пока не будут давать воду около семи вечера. | Don't forget that next month there won't be any water in the daytime. You won't be able to wash up properly until they turn on the water around seven in the evening. |

But when Russians hear such sentences, they tend not to like the imperfective future in the subjoined clause. Instead the perfective future sounds better to them:

| Better sentence | Meaning |

| Не забывай, что в следующем месяце днём не будет воды. Нельзя будет нормально купаться пока не дадут воду около семи вечера. | Don't forget that next month there won't be any water in the daytime. You won't be able to clean up properly until they turn on the water around seven in the evening. |

This is one of those instances where aspect doesn't work quite like we would expect from our beginning textbooks. Frankly, aspect is one of the most consistently tricky parts of the Russian language.

I wish I could say that пока in composition with не should always be translated “until,” but that is simply not the case. Crud. That means I may have to write about two more meanings of пока.

Пока (союз)

The word пока is a conjunction that means “while.” It can be used with verbs in the past, present, or future:

| Папа готовил ужин, пока мама убирала в гостиной. | Dad made dinner while Mom cleaned up the living room. |

| Каждое утро, пока я одеваюсь, брат принимает душ. | Every morning, while I get dressed, my brother takes a shower. |

| Пока я буду в Москве, я буду ходить на занятия йоги два-три раза в неделю. | While I am in Moscow, I will go to yoga classes two or three times a week. |

When пока means “while,” it is essentially synonomous with когда followed by an imperfective verb, although sometimes the пока version sounds a bit better than the когда version, and sometimes it's the other way around. But on the whole all three of the sentences we just saw can be rewritten with когда and mean essentially the same thing:

- Папа готовил ужин, когда мама убирала в гостиной.

- Каждое утро, когда я одеваюсь, брат принимает душ.

- Когда я буду в Москве, я буду ходить на занятия йоги два-три раза в неделю.

In grammatical terms the clause that contains пока is called a subjoined clause. The other clause is called a main clause. A subjoined clause that begins with пока in the “while” meaning must always contain an imperfective verb as its primary verb. The main clause can have either a perfective verb or an imperfective verb.

| Perfective main clause | Imperfective main clause |

| Я взяла водку, пока Женя искал сигареты. | Я разговаривала с мамой, пока Женя искал сигареты. |

| I got the vodka while Gene looked for the cigarettes. | I chatted with Mom while Gene looked for the cigarettes. |

The verb in the main clause simply follows the standard rules for the imperfective/perfective distinction.

What we've written here probably seems way too basic to warrant a blog entry. So why bother? There's a method to this madness. Tomorrow's entry discuss the word пока when it combines with the negative particle не, and that combination often throws people for a loop. You may want to refer back to this entry once you've read the next one to see the contrast.

Качок

Качок is gym slang for a guy who is trying to put on a ton of muscle:

| Как правило качками называют бодибилдеров. | As a rule body-builders are called “качки.” |

For a neat reference of body-building terminology and gym slang, see this forum.

Фамилии-прилагательные

There are many, many Russian last names that end in -ский and its variations. Good students will note that it looks like an adjectival ending, and in fact such names decline exactly like the adjective русский. The first name, of course, still declines just like an ordinary noun. Examples:

| Masculine | Feminine | Plural | |

| Nom | Фёдор Достоевский | Мария Достоевская | Достоевские |

| Acc | Фёдора Достоевского | Марию Достоевскую | Достоевских |

| Gen | Фёдора Достоевского | Марии Достоевской | Достоевских |

| Pre | Фёдоре Достоевском | Марии Достоевской | Достоевских |

| Dat | Фёдору Достоевскому | Марии Достоевской | Достоевским |

| Ins | Фёдором Достоевским | Марией Достоевской | Достоевскими |

Although the last names in -ский are the most common adjectival last names, there are other last names that also decline like adjectives: Толстой declines like молодой; the last name Гладкий declines just like the uncapitalized adjective гладкий; and the last name Поперечный declines just like the uncapitalized adjective поперечный. There aren't very many of these adjectival names that don't end in -ский.

The fun really sets in, though, when you encounter last names that end in -ых or -их in the nominative case, which descended from old genitive plural forms. In these cases the last name itself does not decline, although the first name (and patronymic, if present) does. Examples:

| Masculine | Feminine | Plural | |

| Nom | Константин Седых | Наталья Седых | Седых |

| Acc | Константина Седых | Наталью Седых | Седых |

| Gen | Константина Седых | Натальи Седых | Седых |

| Pre | Константине Седых | Наталье Седых | Седых |

| Dat | Константину Седых | Наталье Седых | Седых |

| Ins | Константином Седых | Натальей Седых | Седых |

Because such last names can be interpreted as masculine, feminine, or plural, not to mention they can be used in any case without a change of ending, interpreting the name in context can tricky. Thus «Я послал телеграмму Седых» could theoretically be interpreted to mean:

- I sent a telegram to [Mr.] Sedykh; or

- I sent a telegram to [Ms.] Sedykh; or

- I sent a telegram to the Sedykhs; or

- I sent [Mr.] Sedykh's telegram; or

- I sent [Ms.] Sedykh's telegram; or

- I sent the Sedykhs' telegram.

In such cases it is wisest to add either a first name and patronymic or some other more specific noun before the last name to clarify the situation: «Я послал телеграмму Константину Седых» or «Я послал телеграмму Наталье Седых» or «Я послал телеграмму семье Седых».

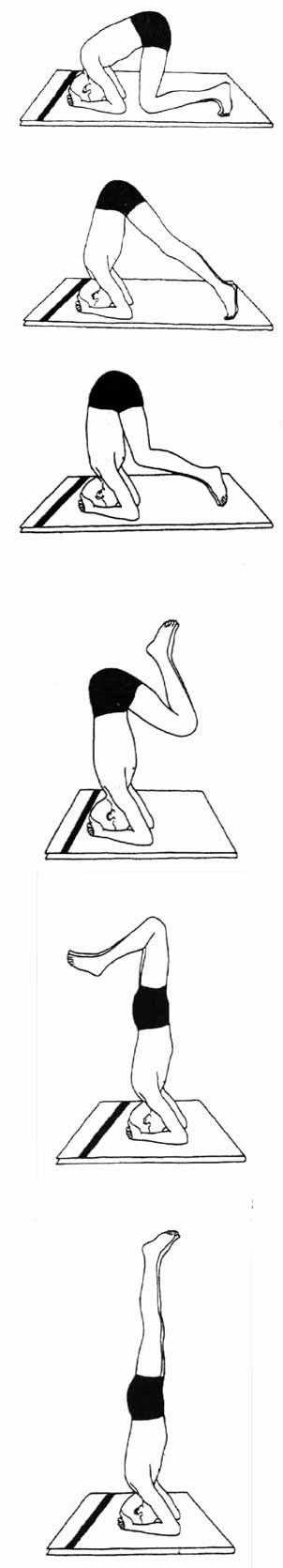

Стойка на голове

The Russian phrase for а hеаdstand is стойка на голове. Examples:

| Каждое утро я по десять минут делаю стойку на голове. | Every morning I do headstand for ten minutes. |

| Мой друг уже около двадцати лет выполняет стойку на голове. | My friend has been doing headstand for twenty years now. |

| Каждое утро я десять минут стою на голове. | Every morning I stand on my head for ten minutes. |

| Вчера я делал стойку на голове, и брат толкнул меня. Теперь болит шея. | Yesterday I was doing a headstand and my brother knocked me over. Now my neck hurts. |

| Если вы боитесь удариться об пол спиной - делайте стойку на голове у стены. | If you are afraid of falling on your back, do headstand at the wall. |

Headstand can be a bit scary if you don't have some good instructions. Here's a set I adapted from the personal website of a Russian businessman-yogi

| Опустись на колени, сплети пальцы рук в замок. | Get down on your knees and weave your fingers together into a locked position. |

| Расположи кисти и предплечья на полу перед коленями для создания опоры. | Place your wrists and forearms on the floor in front of your knees for support. |

| Положи голову макушкой на пол, обхвати ее замком ладоней сзади. | Place the top of your head on the floor and grasp it from behind with your locked fingers. |

| Оторви колени от пола, плавно поднимая таз вверх. | Take your knees of the floor, smoothly raising the pelvis upwards. |

| Медленно перенеси вес тела с пальцев ног на голову и руки. | Slowly transfer your bodyweight from the toes to the head and arms. |

| Плавно подними над полом обе стопы одновременно. | Smoothly raise both feet above the floor simultaneously. |

| Сначала плавно переведи в вертикальное положение туловище с поджатыми ногами, затем бедра и, в заключение, голени ног. | First bring the torso into a vertical position with your legs bent, then [do the same with] the thighs and, finally, the shins. |

| Вытяни ноги к верху и стой на голове так, чтобы все тело было перпендикулярно полу. | Stretch your legs upward and remain on your head so that your whole body is perpendicular to the floor. |

Here's a video of some anonymous geekoid doing a headstand:

And here's a nice graphic of the stages:

<< 1 ... 127 128 129 ...130 ...131 132 133 ...134 ...135 136 137 ... 158 >>