Вешалка

When you enter a Russian apartment, often one of the first things you encounter is an item of furniture on which to hang your coat, and that item is called a вешалка. It's a mostly regular noun, but do notice the fill-vowel in the genitive plural:

| Sg | Pl | |

| Nom | вешалка | вешалки |

| Acc | вешалку | вешалки |

| Gen | вешалки | вешалок |

| Pre | вешалке | вешалках |

| Dat | вешалке | вешалкам |

| Ins | вешалкой | вешалках |

The stem of the word is вес-, which means ‘hang.’ It can apply to a thousand items that are used to hang things: a free-standing coat rack, a peg-board that holds coats, a wire hanger, a hook on a wall, a loop on a shirt, or even a towel-rack:

Various types of вешалки

Sample sentences:

| Как только вхожу в офис, я вешаю свою куртку на вешалку. | I hang my jacket on the coatrack as soon as I enter the office. |

| Почему ты повесил джинсы на вешалку? Надо их погладить, аккуратно сложить и положить в шкаф. | Why did you hang your jeans on the peg board? You should iron them, fold them neatly, and put them in the armoire. |

| — Где мой плащ? — Он как всегда висит на вешалке. Что за идиотский вопрос. |

“Where is my raincoat?” “It's hanging on the coatrack as always. What a stupid question.” |

Поехать

Поехать is the most generic perfective verb that means “to go by vehicle.” Note especially its irregular future and imperative forms.

| to go | |

| Imperfective | |

| Infinitive | поехать |

| Past | поехал поехала поехало поехали |

| Present | No such thing as perfective present in Russian. |

| Future | поеду поедешь поедет поедем поедете поедут |

| Imperative | поезжай(те) |

Поехать is more specialized than ездить in that it always talks about motion in one particular direction; since it is perfective it also focuses on some result of the action:

| Я поехал на Красную площадь и посмотрел на забальзамированное тело Ленина. | I went to Red Square and viewed Lenin's embalmed body. |

In that sentence, the result is that I arrived at the square and thus could view the body.

Поехать can also be used to describe each leg of a multileg journey:

| Я поехал в Подольск, потом я поехал в Климовск, и потом я поехал в Чехов. | I went to Podolsk, then I went to Klimovsk, and then I went to Chekhov. ¹ |

Of course you can do the same thing in the future tense:

| Я поеду в Подольск, потом я поеду в Климовск, и потом я поеду в Чехов. | I'll go to Podolsk, then I'll go to Klimovsk, and then I'll go to Chekhov. |

Now here's something amusing... let's think about this English dialog:

| “Where's Mom?” “She went to the farmers market.” |

Does the second sentence imply that Mom got to the farmers market? No, it doesn't. Here it emphasizes absence from the point of departure while mentioning her intended destination. Likewise in Russian a perfective verb of motion can be used with meaning of “absence from point of departure”:

| — Где мама? — Она поехала на рынок. |

The sentence does not say where Mom has necessarily reached the market, just that she is no longer here.

¹ All three of those places are suburbs of Moscow that you can reach on the электричка on the way to Tula.

Неделя

Неделя is a word that comes from the stem дел- ‘do’ and the negative particle не ‘not.’ It used to mean the day of the week on which you do nothing, in other words Sunday. Bearing that meaning in mind, if you say something happens через неделю “(having passed) through Sunday,” that is in effect saying that it happens the following week. That, I think, is how the old word for Sunday became the modern word for week and now is never used in the meaning of Sunday. It's a regular second declension, soft stem noun:

| Sg | Pl | |

| Nom | неделя | недели |

| Acc | неделю | недели |

| Gen | недели | недель |

| Pre | неделе | неделях |

| Dat | неделе | неделям |

| Ins | неделей | неделями |

When saying that something happened this/last/next week, the preposition на is used with неделя in the prepositional case:

| На прошлой неделе я купил новый французский шампунь и начал мыть им голову. | Last week I bought some new French shampoo and started using it to wash my hair. |

| На этой неделе у меня появилась сыпь, которая покрывает всё темя и весь лоб, мои волосы совсем высохли и начинают крошиться. | This week I've developed a rash that covers the top of my head and my forehead. My hair has completely dried out and is starting to disintegrate. |

| На следующей неделе я остригусь под нуль и буду мазать голову лосьоном, который мне прописал врач. | Next week I'll shave myself bald and start using this lotion on my head that the doctor prescribed me. |

To say something happened a week ago, you use the postposition назад with неделя in the accusative case:

| Неделю назад у меня были красивые, пушистые, блестящие волосы, которые пахли лучше, чем в цветочном магазине. По крайней мере так мне всегда говорили девушки, с которыми я работаю. | A week ago I had beautiful, voluminous, shiny hair that smelled better than a flower shop. At least that's what the girls I work with all told me. |

To say something will happen in a week, use the preposition через with неделя in the accusative case:

| Через неделю я найду себе адвоката. | Next week I'm going to find a lawyer. |

Ехать

Ехать is the determinate (unidirectional) form of the verb ездить “to go by vehicle.” Note especially the odd д that shows up in the present tense forms, as well as its curious command form.

| to go | |

| Imperfective | |

| Infinitive | ехать |

| Past | ехал ехала ехало ехали |

| Present | еду едешь едет едем едете едут |

| Future |

буду ехать будешь ехать будет ехать будем ехать будете ехать будут ехать |

| Imperative | поезжай(те) |

Ехать is more specialized than ездить in that it always talks about motion in progress toward a particular place. Let's say you bump into a friend on the subway. Because you are in a vehicle, you can say:

| — Куда ты едешь? | “Where are you going? |

| — Еду в библиотеку. | “I'm going to the library.” |

| “I'm on my way to the library.” | |

| “I'm heading to the library.” |

Although normally adverbs of frequency and phrases of frequency (like часто and каждый день) usually trigger an indeterminate verb, if the situation describes something that happens regularly on the way to a place, then you use the determinate verb ехать:

| Каждое утро, когда я ехал на метро, мы с Ниной Петровной обсуждали наш любимый телесериал «Санта Барбара». | Every morning, when I was going to work on the subway, Nina Petrovna and I would discuss our favorite soap opera, “Santa Barbara.” |

| Когда я утром еду на работу, я всегда проезжаю мимо Кремля. | Every morning when I go to work, I always pass by the Kremlin. |

| Когда ты будешь ехать по улице Плеханова, ты увидишь справа электростанцию. | When you ride down Plekahnov street, you will spot a power plant on the right. |

One of the curious uses of determinate verbs is that they can be used to say how long it takes to get to a place. From the English-speaking point of view that is rather odd. After all, getting to the place implies a completed action, so we should use a perfective verb, right? But from the Russian point of view in these sentences they are indicating how long the process takes, so the imperfective works:

| Я eхал от дома до работы двадцать минут. | It took me twenty minutes to get to work from home. |

| Сколько минут будем ехать из Министерства здравоохранения до табачной фабрики? | How long will it take us to get from the Ministry of Health to the cigarette factory? |

Ноль, нуль (часть вторая)

The word нуль sometimes occurs in fixed phrases like «начать с нуля» “to start from zero,” which catches the idea of beginning a process with zero previous knowledge or experience or resources:

| Нелла со своей семьёй убежали из Словении в сорок первом году. В конце концов приплыли в США, где им пришлось снова начать свою жизнь с нуля. | Nella and her family fled Slovenia in forty-one. They ended up in the US where they had to start their lives over from nothing. |

| — В январе начну изучать Пушту. — Ты уже немножко говоришь на Пушту, правда? — Нет, начну с нуля. |

“In January I'll start studying Pashto.” “You already speak a bit of Pashto, right?” “Nope, I'll be starting from scratch.” |

Just as in English you can refer to someone as being a complete zero (i.e., being a worthless human being), so also the Russian word can be used in that sense:

| Почему ты ходишь с этим нулём? Он никаких денег не зарабатывает, ни на что не надеется, и вообще не умеет мыться. | Why are you going out with that loser? He doesn't make any money. He doesn't have any dreams. He doesn't even know how to bathe. |

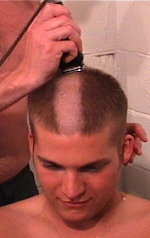

The word is also used to describe a certain haircut «под нуль», that is, “down to zero” or bald. It's the haircut that every draftee receives when joining the Russian army.

| Как только пойдёшь в солдаты, тебя остригут под нуль. |  |

| As soon as you become a soldier, they shave you bald. |

The haircut has become so popular among tough young men that sometimes they are called нули, which is probably best translated as ‘thugs.’ (You can hear the word used that way in the elusively connected song «Главное» “The important thing” by the singer Земфира.)

<< 1 ... 80 81 82 ...83 ...84 85 86 ...87 ...88 89 90 ... 158 >>