Какой

Какой is one of the question words in Russian. It asks a question, so we call it ‘interrogative,’ and in terms of its endings it's an adjective, so we call it an ‘interrogative adjective.’ It declines like this:

| Masc | Neut | Fem | Pl | |

| Nom | какой | какое | какая | какие |

| Acc | * | какую | * | |

| Gen | какого | какой | каких | |

| Pre | каком | |||

| Dat | какому | каким | ||

| Ins | каким | какими | ||

Although какой can be translated several ways, it's most common meaning is “what kind of”:

| — Какие книги ты любишь? — Детективы. |

“What kind of books do you like?” “Mysteries.” |

| — Какой шоколад ты предпочитаешь? — Молочный. |

“What kind of chocolate do you prefer?” “Milk [chocolate].” |

| Какой он человек? Вообще приятный, но иногда он вспыльчивый. |

“What kind of person is he?” “A pleasant guy, on the whole, but sometimes he is hot-headed.” |

| — О каких людях вы пишете? — О тех, кому по жизни не повезло. |

“What kind of people do you write about?” “About those whose lives just haven't worked out right.” |

Sometimes какой has about the same meaning as который, and in those instances we can often translate it as ‘what’ or sometimes ‘which’:

| — Какую книгу ты читаешь? — «Анну Каренину». |

“What book are you reading?” “Anna Karenina.” |

| — Какой автобус нам нужен? — Сто одиннадцатый. |

“Which bus do we need?” “Number one eleven.” |

| — В каком городе вы живёте? — В Уфе. |

“What city do you live in?” “Ufa.” |

| — Какую певицу ты предпочитаешь, Лэди Гагу или Мадонну? — Они обе противны. Я люблю Пинк. |

“Which singer do you prefer, Lady Gaga or Madonna?” “They are both nasty. I like Pink.” |

Ровесники, сверстники, однолетки, одногодки

The word for “someone of the same age” in Russian is ровесник when applied to a man and ровесница when applied to a woman. We have a similar word in English, coeval, but I don't think I've ever heard anyone use it out loud. If the question «Кто из вас старше?» “Which one of you is older?” is directed to a couple of men of the same age, they may respond «Мы ровесники», and if the question is directed to a couple of women, they may respond «Мы ровесницы». If the question is directed to a groups of mixed gender, then the masculine form is used, «Мы ровесники». (By the way, that's generally true in most Indo-european languages. The masculine form of a word often has two roles: the gender-specific masculine meaning, and a generic meaning that can be used for mixed groups.) There is another pair of words, masculine сверстник and feminine сверстница, which mean the same thing and can be used the same way, however they are not quite as common as ровесник/ровесница; they are still pretty common, though.

Of course, if those were the only ways to express the idea, Russian wouldn't be very interesting. Here are some alternatives:

| Мы одного возраста. | Lit., “We are of one age.” |

| Мы однолетки. | Lit., “We are coevals.” |

| Мы одногодки. | Lit., “We are coevals.” |

| Нам по двадцать пять лет. | Lit., “To us are twenty-five years each.” |

The «Мы одного возраста» phrase is perfectly good written and spoken Russian. The phrase with masculine однолеток or feminine однолетка is conversational; I don't recommend writing it. The same holds true for the phrase with masculine одногодок or feminine одногодка.

The phrase with «по» may be the most natural sounding in response to «Сколько вам лет» “How old are you?”, but you wouldn't expect it in response to «Кто из вас старше?»

Подъезд

A подъезд is an entrance hall of a multi-storey house through which all inhabitants pass on the way to their apartments. It’s basically a lobby that usually includes an elevator and has a stairway leading from one floor to the next. Подъезд is composed of two parts, под “under/up to” and езд- “ride.” Here are some example sentences:

| Встретимся около этого подъезда через два часа. | Will meet near this entrance in two hours. |

| В подъезде кто-то опять разбил единственную лампoчку. | Once again, someone broke the only light bulb in the entrance hall. |

| Когда же они наконец перекрасят наш подъезд в нормальный цвет? | When will they finally repaint our entrance hall to a normal color? |

A подъезд is a very important part of the building. Each one has its own distinct attributes that ultimately create a special kind atmosphere that never repeats itself. It can be good or bad, creepy or safe. You can have a roomy apartment with tall ceilings, new windows and a spacious balcony, but that might not be enough to convince someone to buy or rent the place if the подъезд is a mess. Most likely the price will have to drop. How many ordinary people would want, especially at night, to step into a dreary подъезд with one flickering light bulb hanging from the ceiling and barely illuminating the mutilated floor tiles, graffitied walls, bruised mailboxes, and rank, piss-stained stairs?

I grew up in a building with this particular drawback. The six-story structure, built in the Stalin years, was in fair overall condition and at a convenient location: subway station within walking distance and Red Square just a couple of train stops away. For the most part my neighbors were regular people with families and everyday jobs. There was one severe alcoholic living with his mother a floor above my apartment, but he wasn’t the boisterous type and rarely caused trouble. The only real problem was the подъезд that scared visitors and inhabitants alike. One fifteen-year-old girl’s grandmother would not let her come in alone out of certain fears. Of course I thought she was being paranoid, but looking back at it now, it makes a lot more sense. When you have depressed drunkards randomly hanging out by the doorway and occasional junkies shooting up in the shadowy corners, the instinct of caution switches on automatically.

All efforts to bring the подъезд into decent condition failed. Calling the cops didn’t help much either: they got bored—no major disturbances. The neighborhood wasn’t poor by any means, and the house to the left had a nice, clean подъезд, as did the one across the street, but for some strange reason everyone liked to hang out at ours. I also remember a neighbor complaining about having to lower the sale price of her apartment too much. This problem existed in other neighborhoods throughout the city and was eventually acknowledged by the administrators. About four years ago the walls were repainted, new floor tiles laid out, broken mailboxes replaced and, most importantly, a steel door with a phone system was installed. Now there are no uninvited visitors or obvious signs of vandalism, but the urine stench is as strong as ever.

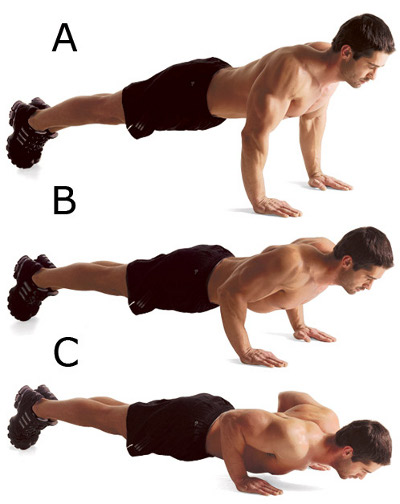

Отжимания от пола (отжиматься)

I'm convinced that everyone who reads this blog is not only an intellectual, but also a person committed to personal fitness and the betterment of the planetary environment, personal moral wisdom, and social justice. So of course all my readers want to know the word for push-ups in Russian. In addition to a noun, the Russians use use the verb отжиматься, which literally means “to press away from.” Verbs can often be turned into nouns by subtracting the -ть and adding -ние. Thus “pressings away from the floor” (push-ups) can be turned into the neuter plural отжимания от пола. Here are examples:

| Каждый день я пятьдесят раз отжимаюсь. | Every day I do fifty push-ups |

| Каждый день я делаю 50 отжиманий. | Every day I do fifty push-ups |

Here's a nice description of how to perform a standard push-up:

| Отжимания от пола | Push-ups |

| Техника выполнения | Technique |

| Ноги слегка расставлены, руки на ширине плеч. Не прогибайтесь в спине, корпус должен составлять одну диагональную прямую. Медленно опуститесь к полу. Если руки прижать к туловищу, нагрузка ляжет на трицепсы. Если локти расположить перпендикулярно к телу, также задействуются грудные мышцы. (source) | Legs are placed slightly apart. Hands are at shoulder-width. Don't flex the back. The body should make a single diagonal line. Slowly lower towards the floor. If you press the arms against the trunk, the load falls on the triceps. If you set the elbows perpendicular to the body, chest muscles will also be activated. |

Total fitness freaks might like this advice:

| Советую делать отжимание в стойке на руках, можно возле стенки. Нужно, чтобы голова коснулась пола, чудесное упражнения для многих мышц, как грудь, спина, трицепс! (source) | I suggest doing push-ups from hand-stand. You can do it next to a wall. The head should touch the floor. It's an excellent exercise for many muscles and the chest, back, and triceps. |

Here's a work-out with one-armed push-ups:

| Я отжимаюсь через день по утрам 30 минут, 4 подхода по 30 раз на кулаках, ноги на стуле, 5,6 подходов на одной руке по 10 раз. После тренировки очень потею, отдышка хорошая. (adapted from this source) |

Every other day for 30 minutes I do 4 sets of 30 on my fists with my feet on a chair, and then five or six sets of ten on one arm. After the work-out I sweat likе crazy, and my breath is normal. |

Just like Americans, young Russian men have to do a lot of push-ups in the army where they will hear:

| Двадцать отжиманий! Быстро! | Twenty push-ups! Quickly! |

One push-up phrase that has become very popular since the nineties is taken from the lips of the General Lebedev puppet on the popular Russian political puppet show «Куклы». Lebedev is quoted often as saying:

| Упал-oтжался! | Down for push-ups! |

Notice the interesting use of the past tense here as a type of command form. That is the strongest form of command possible in Russian; it essentially indicates a complete lack of compassion or respect for the addressee. Don't ever use it in Russia unless you yourself join the Russian army and are hazing recruits to the point of suicide.

Тетрадь

The word тетрадь can be translated as notebook or exercise book, depending on whether it is used for school or not. It is a feminine noun that declines like this:

| Sg | Pl | |

| Nom | тетрадь | тетради |

| Acc | ||

| Gen | тетради | тетрадей |

| Pre | тетрадях | |

| Dat | тетрадям | |

| Ins | тетрадью | тетрадями |

An exercise book is one of the core elements of the Russian education system and is regularly used by students on every step of the scholastic stairway—from preschool to high school. The most popular form of тетрадь used in schools holds about twelve pages, has a thin paper cover and is usually bonded with staples. Graph paper is used for math and lined paper for all other subjects. It’s basically a notebook in which students do their class work exercises and homework assignments. Generally, teachers require students to write with ink and keep everything as neat as possible, or else the grade is lowered. I’ve experienced this downgrading many times.

Example sentences:

| Мама, пожалуйста, купи мне новую тетрадь. | Mom, please buy me a new exercise book. |

| Елена, запиши все детали в свою тетрадь, а то ты всё забудешь. | Elena, write down all the details into your notebook, or else you’ll forget everything. |

| Я даже не знаю, сколько тетрадей я потерял за этот год. | I don’t even know how many exercise books I have lost over this year. |

Тетрадь, especially if it’s a small one, can also be referred to as тетрадка. People often use the two terms interchangeably. Examples:

| Владимир Михайлович схватил мою тетрадку, отошёл к доске, надел свои очки и стал внимательно её рассматривать. | Vladimir Mikhailovich grabbed my exercise book, stepped over to the blackboard, put on his glasses and began to carefully examine it. |

| Перелистав пару страниц, он медленно её закрыл и посмотрел на меня. | After flipping over a couple of pages, he slowly closed it and looked at me. |

| Я знал, что ему не понравятся мои рисунки. | I knew that he wouldn’t like my drawings. |

| — Что? Где же теперь эта тетрадка? | “What? Where is this notebook now?” |

| — Они её конфисковали со всеми остальными бумагами. | “They confiscated it with all the other papers.” |

| — Дурак! Разве я тебе не говорил, чтобы ты эту проклятую тетрадку дома не держал!? | “Fool! Didn’t I tell you not to keep this damned notebook in the house!? |

| — Извини, Вася, я же не знал, что всё так получится. | “Sorry, Vasia, I didn’t know that everything was going to work out this way.” |

<< 1 ... 96 97 98 ...99 ...100 101 102 ...103 ...104 105 106 ... 158 >>