Categories: "Medicine"

Рука, часть четвёртая

As mentioned in previous entries, the most common word for arm/hand in Russian is рука. What if you want to be more specific?

First off, the actual hand is called кисть, which is a feminine noun. It includes запястье the wrist, пястье (the area from the wrist to the first knuckle of each finger, which is also called пясть... heck, do we even have a word for that in English?), and пальцы “the digits.” I say “digits” here because the word палец can mean either finger or toe. If you want to specify fingers, then you say пальцы рук, and if you want to specify the toes, you say пальцы ног.

Next we have the forearm предплечье, in which the major bones are the radius лучевая кость (literally “the ray bone”), which is the bone on the same side of the arm as the thumb, and the ulna локтевая кость (literally “the elbow bone”). I think the average American doesn't know the words radius and ulna. The Russian phrases are a bit more descriptive than the Latinate English equivalents. I wonder if the average Russian knows the names of those bones in Russian? Maybe we'll be fortunate and a native will add a comment about that to this post.

Moving on up we have the elbow локоть, a masculine word, whose second о is a fleeting vowel, thus genitive локтя.

Moving farther up we have плечо, which can mean either the shoulder itself, or it can mean collectively both the shoulder and the upper arm. The bone in the upper arm is плечевая кость, literally “the shoulder bone.” That sounds funny to us Americans. Although the proper name of the bone is “the humerus,” there is a song called “Dry Bones” that contains a line “the arm bone's connected to the shoulder bone;” it sounds amusingly folksy. Even humorous… pun intended.

Last but not least, the English word palm means the front side of what the Russians call пястье. Isn't that curious? We have a word in English that describes the area from the wrist to the first knuckles of the fingers as understood from the front side of the hand, but we don't have a word that describes it from the back side. The Russian word for palm is ладонь, which is a feminine noun. Isn't that curious? Both languages have a word for that part of the hand as considered from the front side. Russian has two words (пястье & пясть) for that part of the hand as considered from either side, but English has no such word. And both languages (as far as I know, correct me if I'm wrong) do not have a single word describing that part of the hand as considered solely from the back side.

Finally, Russian has a conversational term they use sometimes, пятерня, which means “the palm and the fingers,” i.e. what we English speakers usually call the hand, but пятерня is used much, much less often than рука.

Рука, часть третья

As mentioned before, рука can be translated 'hand' and 'arm.' Sometimes that distinction will be reflected in the choice of за and под: use with за usually indicates 'hand,' and под 'arm.' For instance:

| Она взяла меня за руку и повела в церковь. | She took me by the hand and led me to church. |

| Я почти не мог ходить. Папа взял меня под руку и отвёл меня к медсестре. | I could barely walk. Dad took me by the arm [supported me under the arm] and took me to the nurse. |

| Мы пошли домой, держась за руки. | We headed home hand in hand. |

| Мы пошли домой под руку. | We headed home arm in arm. |

Hand in hand, arm in arm… Russians are not nearly as freaked out about physical contact as we Gringos are. Male friends can walk arm in arm without any connotation of romantic involvement. Female friends often walk hand in hand without anyone thinking twice about it.

I remember the first time I was in Russia, 1986, I was interested in the fate of the баптисты. Баптист at the time was the closest equivalent to "Evangelical Christian." At church one Sunday I passed a Bible off to a Russian guy. (They were still not all that easily available then.) We ended up talking; I was invited to his home. After dinner he escorted me back to the subway station, and then eventually all the way back to the university. As we sat in the subway car, he threaded his arm through my arm; that by itself was odd for me as an American man. But when he got to a sensitive part of the conversation, he leaned over to whisper; as he whispered I could feel his lips moving inside my ear. Fortunately I had been taught that Russians have very different perceptions of personal space and contact, so I didn't overreact. I should say that this was not typical. None of my other Russian acquaintances have ever been quite that touchy-feely. The important thing is to give people the benefit of the doubt when you first experience a new culture first hand.

There are other entries about the word рука in this blog. Click on the 'ruka' category to find them.

Рука, часть вторая

Since рука means both 'arm' and 'hand,' the Russians use other means to distinguish which part of the arm/hand is involved, and often this involves a distinction between the prepositions в and на. If the preposition в is involved, it usually correlates to 'hand' in English; if на, then 'arm.' For instance:

| В руке она держала ключ от новой машины. | In her hand she held the key to a new car. |

| На руках он держала сына брата. | She held her brother's son in her arms. |

You'll notice that those sentences used the prepositional case; that's because they expressed the location of the thing being held. Russian usually distinguishes motion phrases and location phrases. So if you want to take things into your hands/arms, you end up using the accusative case:

| Она взяла котёнка в руки, и котёнок лизнул её в нос. | She picked up the kitten [and held it in her hands], and the kitten licked her nose. |

| Она взяла котёнка на руки, и котёнок лизнул её в щёку. | She picked up the kitten [and held it in her arms], and the kitten licked her cheek. |

| Я взял племянника на руки, и он срыгнул на мою рубашку. | I picked up my nephew [and held him in my arms], and he spit up on my shirt. |

More importantly, if you want to take someone in your arms, the best way to say it is with the verb обнимать/обнять 'to embrace, hug' which you can use without even mentioning руки: «Я её обнял» “I hugged/embraced her.”

For other entries about the word рука, click on the 'ruka' category.

Рука, часть первая

Why does it seem like all the simplest Russian words are complicated? The Russian word рука is usually used in the contexts when English speakers would use the word hand, but it doesn't really mean hand. It means both the hand and the lower and the upper arm. Some other languages do that as well, Ancient Greek, for instance. When Doubting Thomas said

Except I shall see in his hands the print of the nails, and put my finger into the print of the nails, and thrust my hand into his side, I will not believe.

he used the word χείρ for hand which also means both hand and lower arm. Christ's nail wounds might well have been in the forearms or wrists, not the hands.

The stress shifts quite a bit in the forms of this word, depending on case:

| Sg | Pl | |

| Nom | рука | руки |

| Acc | руку | руки |

| Gen | руки | рук |

| Pre | руке | руках |

| Dat | руке | рукам |

| Ins | рукой | руками |

Very often when рука combines with a short preposition, the stress shifts to the preposition itself: за руку , на руку, рука об руку, под руку.

Since the word means more than "hand," English equivalents of Russian sentences may have either "hand" or "arm" in their translations. Join me again over the next few days for more detail about рука in phrases.

Other entries about the word рука will be forthcoming. Click on the 'ruka' category to find them as they appear.

Похмелье

Every American college student should go to Russia. It's just such a great experience. Russian friendships are intense. The Russian countryside is gorgeous. Astonishing museums and architecture. There are beautiful churches in which to pray and contemplate what good works we might like to accomplish over the next year. Ah, such opportunities! So why is it that those American students always end up drinking obscene amounts of vodka, throwing up at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, singing “Rubber Ducky” with a German accent in the middle of Red Square at three in the morning in the company of some Russian ballet dancer they've been flirting with since eight in the evening at the Irish Bar on the Arbat? And in the morning they wake up with похмелье, a hangover.

A smarmy American might even suggest that we have a spiritual obligation to get at least one hangover in Russia since the Primary Chronicle quotes Vladimir the First as rejecting Islam because the Russians love to drink, and thus to really get into the spirit of Russian language study, you have to tie one on. Wow, a little education and we can justify just about anything.

“I have a hangover” in literary Russian is «У меня похмелье» or «Я с похмелья». Notice that с here is followed by the genitive case, not the instrumental. It is incorrect to say «Я с похмельем». You'll also hear the more conversational «Я с бодуна», which means the same thing. Here are a couple sample sentences:

| Я по субботам работаю с похмелья. | On Saturdays I work with a hangover. |

| Почему с похмелья люди сильно и много чихают? | Why do people with hangovers sneeze so much and so strongly? |

Actually, I doubt hangovers have anything to do with sneezing. Probably they just encountered a drunk with a cold.

You might think that people would battle hangovers with the obvious solution: sobriety. Nope. There is an incredible wealth of material out there discussing the question «Как опохмелиться наилучшим способом?» “What is the best method to cure a hangover?” More precisely, the verb опохмеляться-опохмелиться mostly means “to treat a hangover by using more alcohol,” or as some people say in English “to take a hair of the dog that bit you.”

Russians can discuss this question for hours and hours on weekends… weekends with bloodshot eyes and aching heads and the taste of dachsund fur and horseradish in their mouths. There is even a website devoted to the issue. Here is an actual answer to the question I found on the web:

| Как опохмелиться наилучшим способом? | What is the best method to cure a hangover? |

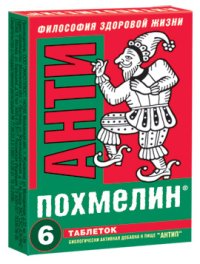

| хм....серьезную тему для обсуждения поднял товарисч....сложно даж так сразу ответить...скажу одно, что нажравшись в жопу, с дикого похмелья мало что поможет...сказки по типу выпить бутылку пива- полный бред...мне нравиццо кефиром, хотя уж не всегда помогает, я считаю лучше всего не доходить до похмелья, т.е. пить перед нажираловкой АНТИПОХМЕЛИН, 3 таблетки перед нажираловкой, и скоко ни пей будешь как огурчик... оч рекомендую, вещь реально действует (source) | hm... the komrade raised a serious issue for discussion... it's hard to come up with a quick answer... i'll just say that once you've gotten drunk off your ass and have a raging hangover not much can help you... stories like “drink a bottle of beer” are complete fantasies... i like 2 use kefir, although it doesn't always help, and i think the best way is to not get all the way to the hangover, i.e. before getting down to the heavy boozing take Antipokhmelin, three tablets before saucing up, and no matter how much ya drink, you'll be fit as a fiddle... v m recommend, stuff actually works |

The guy's spelling suggests he was actually writing with a hangover «он писал с похмелья». I thought he was making up the Антипохмелин, but apparently it's a real product. You can see a picture of it at the right.