«Последний тост» Анны Ахматовой

In June I came across a poem by Anna Akhmatova that was new to me. I disliked the translation that was presented with it, so I decided to make a new one. To go about the process, I began with a word for word gloss next to the original:

Анна Ахматова |

Anna Akhmatova Last toast |

Я пью за разорённый дом, |

I drink to the destroyed home To my cruel life To loneliness two-together And to you I drink |

За ложь меня предавших губ, |

To the lie of lips that betrayed me To the dead cold of eyes To the fact that that world is harsh and crude To the fact that God did not rescue |

| 27 июня 1934, Шереметьевский Дом | June 27, 1934 Sheremetev Palace |

I wanted my final translation to reflect the original rhyme scheme, but I couldn't come up with any lines with “did not rescue” or “did not save” that flowed in neat iambs, so I eliminated the “not” approach and rephrased it in the positive with “God let this be.” With that established, I could then work backwards so that all the previous lines would lead up to it. Here's what I came up with:

The Last Toast

Here's to our family, now in shatters

And here's to all my cruel days

The loneliness of two in tatters

And cheers to you and all your ways

Here's to the lips that fin'lly cheated

To cold dead eyes that cannot see

A world where justice is not meted

And cheers to God that let this be

June 27, 1934

Sheremetev Palace

What can we say about this translation? It captures the bitterness and despondency which are the essence of the original. That by itself makes it a decent translation. It flows decently in English. That makes it a good translation. It captures the irony of each line of the toast, and it approximates the ABAB rhyme scheme of the original. That combination of successes makes it a very good translation.

Notes:

- I am not an Akhmatova scholar and have never properly researched her life, so it is entirely possible that my translation misses autobiographical references from the original.

- Akhmatova lived in an apartment in the garden wing of Sheremetev Palace on the Fontanka embankment from the mid 1920s till 1952. (Wikipedia)

- If you are interested in poetic translation as a topic, you can see some variations I played with here.

- The third line means “to the loneliness of two together.” It is so concisely put in Russian that I don't know of any way to capture its punchiness in English. The word одиночество contains the root один one, and “two together” contains the stem дв- ‘two,’ and the contrast between them is heart-rendingly obvious in Russian. (The English word ‘lonely’ also comes from a phrase that used to mean “all one,” but we no longer feel the ‘one’ part of the word as clearly as the Russians understand один in одиночество.) The only option is to find some phrase in English that gathers heartbreak neatly. “In tatters” is my best attempt.

- Line 7 is the one most open to criticism. It is only loosely connected with the original in that a world without justice is ipso facto a cruel world. Doubtless I will be accused of отсебятина. If anyone can come up with a line to replace it, making whatever other adjustments are necessary for the poem to work, I'd love to see it.

- The word “cheated” in line 5 will be first interpreted by the English reader as meaning spousal cheating. If upon study it turns out that it was betrayal that had nothing to do with the marital relationship, then the line needs to be rewritten. That of course means the rhyme in line 7 will most likely have to change as well.

- Feel free to add your own translation in the comment section.

Писатель

Alexander Pushkin is a писатель. Franz Kafka is a писатель, and so is Hemingway, along with that lady who wrote “Twilight.” The word писатель derives from the verb писать (write) and as you might have already guessed, is translated as writer. Писатель is a masculine term used to refer to male writers and писательница refers to female writers. But nowadays it’s not unusual to hear a woman be called a писатель.

| Sg | Pl | |

| Nom | писатель | писатели |

| Acc | писателя | писателей |

| Gen | писaтеля | писателей |

| Pre | писaтелe | писaтеляx |

| Dat | писaтелю | писaтелям |

| Ins | писaтелeм | писaтелями |

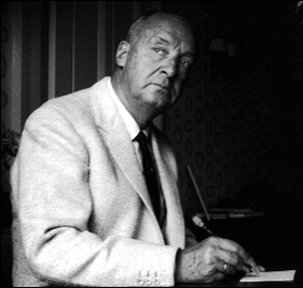

One of the best-known and most controversial писателей of the twentieth century, Vladimir Nabokov, at work.

| Пауло Коэльо является одним из самых популярных писателей нашего времени. | Paulo Coelho is one of the most popilar writers of our time. |

| При жизни ирландский писатель Брэм Стокер был малоизвестен, но теперь все знают его произведение «Дракула». | During his life Irish writer Bram Stocker was fairly unknown, but now everyone knows his work “Dracula.” |

| Я никогда не думал, что Кирилл станет таким хорошим писателем и напишет столько книг. | I never thought that Cyril would become such a good writer and write so many books. |

| Oн необычный писатель c интересными идеями, но, к сожалению, не может найти издателя для своих произведений. | He is an unconventional writer with interesting ideas, but unfortunately he can’t find a publisher for his works. |

Пойти

The next generic verb of motion is пойти. Note especially its irregular past tense forms.

| to go | |

| Perfective | |

| Infinitive | пойти |

| Past | пошёл пошла пошло пошли |

| Present | No such thing as perfective present in Russian. |

| Future | пойду пойдёшь пойдёт пойдём пойдёте пойдут |

| Imperative | пойди(те) |

Пойти is more specialized than ходить in that it always talks about motion in one particular direction; since it is perfective it also focuses on some result of the action:

| Я пошёл в аптеку и купил аспирин. | I went to the pharmacy and bought aspirin. |

In that sentence, the result is that I arrived at the pharmacy and thus could make my purchase.

Пойти can also be used to describe each leg of a multileg journey:

| Я пошёл в аптеку, потом я пошёл на рынок, и потом я пошёл домой. | I went to the pharmacy, then I went to the market, and then I went home. |

Of course you can do the same thing in the future tense:

| Я пойду в аптеку, потом я пойду на рынок, и потом я пойду домой. | I'll go to the pharmacy, then I'll go to the market, and then I'll go home. |

Now here's something amusing... let's think about this English dialog:

| “Where's Mom?” “She went to the store.” ¹ |

Does the second sentence imply that Mom got to the store? No, it doesn't. Here it emphasizes absence from the point of departure while mentioning her intended destination. Likewise in Russian a perfective verb of motion can be used with meaning of “absence from point of departure”:

| — Где мама? — Она пошла в магазин. |

The sentence does not say whether Mom has necessarily reached the store, just that she is no longer here.

¹ In terms of the classical description of English grammar, this sentence should be, “She has gone to the store.” For some English speakers that is still the best version of the sentence, but the English present perfect is slowly being replaced by the simple past, so “She went to the store” sounds perfectly normal for many speakers of American English.

Столица

Столица is the Russian word for capital, as in a capital city, not a capital letter. It's a perfectly regular noun (as long as you know the five-letter spelling rule).

| Москва — столица Российской Федерации. | Moscow is the capital of the Russian Federation. |

| — Вашингтон — это столица какой страны? — Не помню. Посмотри в Википедии. |

“Washington is the capital of what country?” “I don't remember. Look it up on Wikipedia.” |

| Столица Аризоны — Финикс, хотя раньше столицей был город Прескотт. | The capital of Arizona is Phoenix, although previously the capital was Prescott. |

| До столицы ещё оставалось пятьдесят километров, когда у нас лопнула шина. | We were fifty miles away from the capital when our tire blew out. |

Note: for a reminder on the difference between capital and Capitol, see the first usage note at dictionary.reference.com.

Газировка

The Russian word газировка is a slang term for газированная вода (carbonated water) and can be translated as soda. At one point it was almost synonymous with various soft carbonated drinks like Тархун, Буратино, Дюшес, Байкал, and so on... Now people tend to go by the brand’s name, especially when it comes to the popular Coke and Pepsi products.

In the Soviet days and even the early nineties, one could often spot special self-service soda fountains on city streets and public areas like airports, train stations, parks, farmer markets, and etc. The bulky, rectangular apparatuses were similar to the vending machines of today; you’d insert a kopeck or two and select the desired drink (sweet drinks cost more). There were no bottles or cans, every machine had a reusable стакан (glass) that was to be rinsed off with water in a special compartment and then used for the газировка. On a hot afternoon there could be a line of people standing next to the soda machine, each patiently waiting to quench his tormenting thirst. If lucky, you could hear one of these glasses shatter on the pavement and then find out that it was the last one, or better yet you could absorb some of your predecessor’s germs. For some reason I still miss those machines, although since then have been turned into scrap metal and become part of Soviet-era nostalgia. How awesome would it be to just have one in your kitchen right now?

This is an image of a typical Soviet-era self-service soda machine. It's one kopeck for plain carbonated water and three kopecks for the water to be mixed with sweet syrup.

Here are some example sentences with газировка:

| Эта женщина меня случайно толкнула, и я пролил всю свою газировку на господина Мечниковa. | That woman accidentally pushed me and I spilled all of my soda on mister Mechnikov. |

| Летом Mиша любит пить холодную газировку и есть мороженое. | In the summertime, Misha likes to drink cold soda and eat ice-cream. |

| Hекоторые врачи говорят, что любая газировка очень вредна для здоровья. | Some doctors say that any kind of soda is very bad for the health. |

| Aмериканцы пьют намного больше газировки, чем русские и немцы. | Americans drink a lot more soda than Russians and Germans. |

<< 1 ... 84 85 86 ...87 ...88 89 90 ...91 ...92 93 94 ... 158 >>