Categories: "Numbers"

Два/две (часть вторая)

The other day we mentioned that the words два/две ‘two’ are followed by a noun in a form that resembles the genitive singular. What's really freaky, though, is that if you put an adjective between the number and the noun, you don't use the genitive singular. So what for do you use? Well, that depends...

If you are dealing with masculine or neuter nouns, then you have to use an adjectival form that copies the genitive plural:

| два новых стола | two new tables |

| два длинных письма | two long letters |

If you are dealing with feminine nouns, it is usually best to use an adjectival form that copies the nominative plural:

| две новые машины¹ | two new cars |

Here are some sample sentences:

| На поле лежали два раненых солдата. | Two wounded soldiers lay in the field. |

| У инопланетянина были два чёрных глаза и один зелёный. | The alien had two black eyes and one green one. |

| Две красивые туристки беседовали за шампанским. | Two pretty tourists were chatting over champagne. |

| У меня два младших брата. | I have two younger brothers. |

¹ You will sometimes also encounter две новых машины, аlthough новые is better style these days.

Два/две (часть первая)

Every student of the Russian language knows that Russian nouns have a singular form and a plural form. Many don't know that a thousand years ago those nouns had a “dual form” as well. The dual meant “two of an item”, whereas the plural meant “more than two of an item”. Thus града meant “two cities” and сътѣ meant "two hundreds" and сестрѣ meant “two sisters”. At that time the number дъва was an adjective that agreed with masculine dual nouns and emphasized twoness, and дъвѣ was an adjective that agreed with neuter/feminine nouns and emphasized twoness as well. So back then we had дъва града “two cities”, дъвѣ сътѣ “two hundreds”, and дъвѣ сестрѣ “two sisters”.

Over the centuries time/entropy/life disrupted all that beautiful grammatical symmetry. The "-a" form of masculine nouns often resembled the genitive singular, so nowadays the numbers два/две are followed by nouns in a form that generally coincides with the genitive singular form. The gender association of the numbers shifted as well: nowadays два is used with masculine and neuter nouns, and две is only used with feminine nouns. Here are some sample sentences:

| Дважды два — четыре. | Two times two is four. |

| У меня два брата, которые постоянно издеваются надо мной. | I have two brothers who constantly make fun of me. |

| Когда я был ребёнком, на меня наехали две машины, я пролежал в больнице три месяца. | When I was a child, I was run over by two cars, and I lay in the hospital for three months. |

| — Как зовут твою девушку? — Какую? У меня две девушки. — Какой ты бабник! |

"What's your girlfriend's name?" "Which one? I have two girlfriends." "You are such a player!" |

Миллиард

Let's say a young Russian student is composing an essay and decides to write “I want to earn a billion dollars” in Russian. He knows the word for million is миллион, so he figures a billion must be биллион, but, being an enterprising student, he quickly double-checks his Russian dictionary. He is pleased to note that the word is exactly as he expected, so he writes «Я хочу заработать биллион долларов.» Alas, he has made an error. Even though you can find the word биллион in Russian dictionaries, people rarely use it. Instead they say миллиард:

| Я хочу заработать миллиард долларов. | I want to earn a billion dollars. |

| Бюджет штата Аризона уменьшили на два милларда долларов. | The Arizona state budget has been reduced by two billion dollars. |

| У бывшего премьера Таиланда отобрали полтора миллиарда. (source) | One and a half billion dollars have been confiscated from the former Prime Minister of Thailand. |

| Минобороны потратило пять миллиардов рублей на неудачные испытания беспилотников. (source) | The Ministry of Defense has spent five billion rubles on unsuccessful drone aircraft experiments. |

If you are translating from English to Russian, you must be quite careful if the source document has the word billion in it. In the US the word billion always means 1,000,000,000. That's not necessarily true in other English-speaking countries. For most of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries in England the word meant 1,000,000,000,000. (In the States we call that a trillion). The US system is known as the “short scale” system of naming numbers, and the old British version is known as the “long scale.” In 1974 the UK officially switched from long scale to short scale, but there are still people in Britain who use the word the other way. That means that a good translator will take the time to determine the nationality of the author and the country in which the source was published before he finalizes his translation, and even then it's a good idea to see if the source document has some internal confirmation of which meaning is intended.

Часы

The word часы means a watch or a clock. It has no singular form, only plural; such nouns that lack singulars we label “pluralia tantum.” It declines likes this:

| Pl | |

| Nom | часы |

| Acc | |

| Gen | часов |

| Pre | часах |

| Dat | часам |

| Ins | часами |

Since the word only has plural forms, the pronouns that refer to it must also by in the plural:

| Какие красивые часы! Где ты их купил? | What a beautiful watch! Where did you buy it? |

| Я раньше не носил часов, но теперь я жить без них не могу. | I didn't use to wear a watch, but now I can't live without one. |

| — Сколько сейчас времени? — По моим часам уже два часа, но они часто отстают. Может быть и попозже. |

“What time is it?” “It's already two o'clock according to my watch, but it often runs slow so it might be a bit later.” |

| Мне нужны новые часы, мои старые всегда спешат. | I need a new wach. My old one always runs fast. |

Since the word only occurs in the plural, you might wonder how to say “one watch.” Easy: you use the plural of the number one!

| — Сколько ты купил часов? — Только одни часы и два ремешка к ним. |

“How many watches did you buy?” “Just one watch and two watchbands to go with it.” |

If you are talking about two, three, or four watches, then двое, трое and четверо can be used:

| Наша семья очень любит часы. У меня двое часов, у брата трое часов, а у сестры целых четверо. | Our family really likes watches. I have two watches. My brother has three watches, and my sister has no less than four.¹ |

These collective numbers don't combine very well with the other ordinal numbers. That is, don't try to say something like:

| двадцать одни часы | twenty-one watches |

| двадцать двое часов | twenty-two watches |

| двадцать трое часов | twenty-three watches |

| двадцать четверо часов | twenty-four watches |

In these circumstances it is best to add the word штука ‘unit’ to the phrase:

| Наш клуб купил двадцать одну штуку подарочных часов. | Our club purchased twenty-one watches. |

| Наш клуб купил двадцать две штуки часов | Our club purchased twenty-two watches. |

| Наш клуб купил двадцать три штуки часов | Our club purchased twenty-three watches. |

| Наш клуб купил двадцать четыре штуки часов | Our club purchased twenty-four watches. |

Some Russians allow the use of the word пара ‘pair’ in place of штука:

| Наш клуб купил двадцать одну пару часов. | Our club purchased twenty-one watches. |

| Наш клуб купил двадцать две пары часов | Our club purchased twenty-two watches. |

| Наш клуб купил двадцать три пары часов | Our club purchased twenty-three watches. |

| Наш клуб купил двадцать четыре пары часов | Our club purchased twenty-four watches. |

I say “some Russians” because to some other Russians that type of phrase sounds like просторечье “substandard speech” (see Rosenthal's commentary). If you want to be sure you sound okay, use the штука approach.

¹ Yes, yes, I know that one properly is supposed to say “no fewer than four,” but frankly “no less than four” is the way most Americans will say it nowadays, even educated ones. “No fewer than four” sounds forced and unnatural, as if someone with a mediocre education is trying to prove that he isn't ignorant.

Ноль, нуль (часть вторая)

The word нуль sometimes occurs in fixed phrases like «начать с нуля» “to start from zero,” which catches the idea of beginning a process with zero previous knowledge or experience or resources:

| Нелла со своей семьёй убежали из Словении в сорок первом году. В конце концов приплыли в США, где им пришлось снова начать свою жизнь с нуля. | Nella and her family fled Slovenia in forty-one. They ended up in the US where they had to start their lives over from nothing. |

| — В январе начну изучать Пушту. — Ты уже немножко говоришь на Пушту, правда? — Нет, начну с нуля. |

“In January I'll start studying Pashto.” “You already speak a bit of Pashto, right?” “Nope, I'll be starting from scratch.” |

Just as in English you can refer to someone as being a complete zero (i.e., being a worthless human being), so also the Russian word can be used in that sense:

| Почему ты ходишь с этим нулём? Он никаких денег не зарабатывает, ни на что не надеется, и вообще не умеет мыться. | Why are you going out with that loser? He doesn't make any money. He doesn't have any dreams. He doesn't even know how to bathe. |

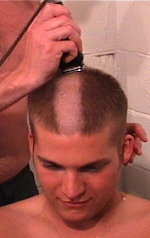

The word is also used to describe a certain haircut «под нуль», that is, “down to zero” or bald. It's the haircut that every draftee receives when joining the Russian army.

| Как только пойдёшь в солдаты, тебя остригут под нуль. |  |

| As soon as you become a soldier, they shave you bald. |

The haircut has become so popular among tough young men that sometimes they are called нули, which is probably best translated as ‘thugs.’ (You can hear the word used that way in the elusively connected song «Главное» “The important thing” by the singer Земфира.)