Categories: "Food"

Кофейня

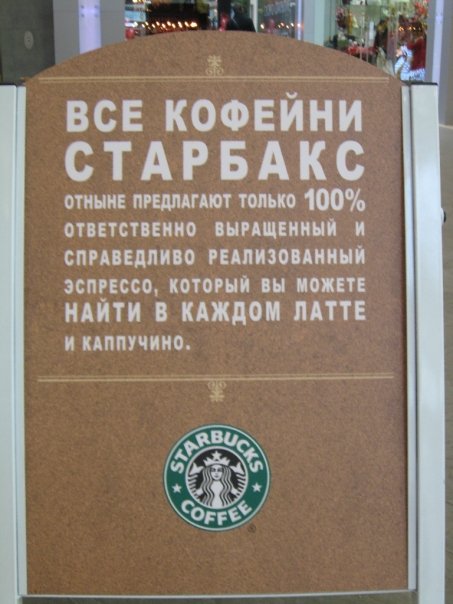

A small restaurant where they sell кофе is called кофейня, and its genitive plural is кофеен. Doubtless the most well known coffee trademark is Starbucks, and sure enough you can even find their shops in Russia nowadays. Here's a sign from one of their outlets:

The sign reads: “The espresso you find in each Starbucks latte and cappucino is 100% responsibly grown and fairly traded.”

If you are up for a challenge, here are two linguistic tasks for you:

- You will notice the English translation does not match word for word with the Russian original. See if you can come up with a translation that matches the original more closely word for word and yet still sounds good in English.

- You will notice that the word еспрессо ends in an -о but shows masculine adjectival agreement. Present a hypothesis as to why that is.

Post your translations and hypotheses to the blog using the comment links.

Кофе

The Russian word for coffee is кофе. It's an indeclinable noun, which means it never changes its ending for case or number. Despite the ending, it's a masculine noun, not a neuter one. In other words, one is supposed to say чёрный кофе, not чёрное кофе. There is a reason for that: the word used to be кофей, which is clearly masculine. In fact, if you read Crime and Punishment in Russian, you will still find it spelled that way.

You know how in English data is supposed to be plural, but everyone uses it as a singular form? That is, we are supposed to say “These data are interesting,” but in fact we usually say “This data is interesting”? The Russians are in a similar situation with the word кофе. Theoretically it's masculine, but it's incredibly common to hear it as a neuter. The error is so widespread that it has spawned a well-known joke:

| К буфетчице постоянно подходили покупатели, которые просили одно кофе. | At the snackbar customers would constantly ask the clerk for одно coffee. |

| Каждый раз она с досадой думала: | Each time she would get irritated and think: |

| «Что за безграмотность! | “What illiteracy! |

| Хоть бы раз в жизни услышать нормальное один кофе.» | Just once in my life I'd like to hear a proper один кофе. |

| Вдруг к ней обращается иностранец: | Suddenly a foreigner walks up to her and says: |

| «Мне, пожалуйста, один кофе…». | I'd like один coffee, please…” |

| Буфетчица с удивлённой радостью смотрит на него, | The clerk looks at him with surprise and joy, |

| и он добавляет: «…и один булочка.» | and then he adds “and один sweet roll.” |

The last line is funny because in that context a Russian will say одна булочка; thus the foreigner accidentally got the grammatically tricky point right, but then he slaughtered the Russian language by making a mistake that no native speaker, not even the least educated, would ever make.

This joke is retold all over Russia in a thousand variations where the customer changes: often he's a Georgian because the Georgian accent is well known and commonly mocked, sometimes a Russian, sometimes a foreigner, and the jokes are sometimes written with funky Russian spelling to portray his non-Russian accent.

Update 2009-09-02: As of yesterday a decree of the Russian Ministry of Education and Science went into effect that affirms several dictionaries as normative for Russian as the official language of the Russian government. Those dictionaries acknowledge that кофе can be treated as neuter, so in a sense it is now officially acceptable to say чёрное кофе. The dictionaries include:

- "Орфографический словарь русского языка" Б.Букчиной, И.Сазоновой и Л.Чельцовой

- "Грамматический словарь русского языка" под редакцией А.Зализняка

- "Словарь ударений русского языка" И.Резниченко

- "Большой фразеологический словарь русского языка" с комментарием В.Телия

Мясо

Russians often use the word мясо to mean “red meat,” so if you say «Я не ем мясо» or «Я не ем мяса», you may still be served chicken or fish. “Vegetarian” is вегетарианец or вегетарианка.

| Вегетарианцы не употребляют в пищу мясо, птицу, рыбу и морепродукты животного происхождения. | Vegetarians don’t eat meat, poultry, fish or seafood of animal origin. |

| Я не ем ни мяса, ни рыбы, ни птицы уже почти 9 лет. | I haven’t eaten meat, fish or poultry for almost nine years now. |

When talking about мясо, Russian usually distinguishes between the live animal and the meat on your plate by adding the suffix -ина. Here are some common ones:

| Animal | Животное | Мясо | Meat |

| cow | говядо * | говядина | beef |

| pig | свинья | свинина | pork |

| ram | баран | баранина | mutton |

| calf | телёнок | телятина | veal |

| deer | олень | оленина | venison |

The word for “ham” is ветчина, from the adjective ветхий “old,” the opposite of свежий “fresh.”

The suffix –ина is productive, which means you can use it to make interesting meat out of just about any mammal.

| Из-за Олимпиады китайцам временно запретят готовить собачину. | Because of the Olympics, the Chinese are being temporarily forbidden from preparing dog meat. |

| А вот если добавить к мясу кусок конины, бульон будет намного вкуснее. (source) | If you add a piece of horse meat to the meat, the bouillon will be much tastier. |

| При посещении страны, где мясо слона в том или ином виде фигурирует в ресторанных меню, вы можете попробовать и тушеную слонину. | If you visit a country where the meat of the elephant appears on restaurant menus in one form or other, you might try stewed elephant meat. |

| Когда-то было прогрессивным есть человечину, потому что в ней полно белка. (source) | At one time it was considered progressive to eat human meat because it has a lot of protein. |

Hungry?

* Говядо is the Old Russian word for cow. Nowadays we say корова.

Пирожки

Today I'd like to write about пирожки (singular пирожок), a word maybe as famous as матрёшка ![]() , although the former belongs to the food category and is not a souvenir as the latter. Russian cuisine is famous for its doughy things, and пирожки are among them. Basically, it is dough with filling inside. The filling can be anything: berries, mushrooms, roots, vegetables… anything you wish to put in there. The dough is not a simple dough, however, but a little complicated to make, and it takes time to master the skill of preparing it. In Russian it is called сдобное тесто. Recipes vary, but the thing they all have in common is that they have yeast, and and the dough takes time to rise. Many great Russian authors, e.g. Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, Chekhov, Paustovsky, and Turgenev, numerous times mention in their writings the process of making the dough for pirozhki (or for bliny, like Сhehov, who wrote a special short story about it, «О бренности»; see «Как испечь блины по-чеховски?» for details

, although the former belongs to the food category and is not a souvenir as the latter. Russian cuisine is famous for its doughy things, and пирожки are among them. Basically, it is dough with filling inside. The filling can be anything: berries, mushrooms, roots, vegetables… anything you wish to put in there. The dough is not a simple dough, however, but a little complicated to make, and it takes time to master the skill of preparing it. In Russian it is called сдобное тесто. Recipes vary, but the thing they all have in common is that they have yeast, and and the dough takes time to rise. Many great Russian authors, e.g. Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, Chekhov, Paustovsky, and Turgenev, numerous times mention in their writings the process of making the dough for pirozhki (or for bliny, like Сhehov, who wrote a special short story about it, «О бренности»; see «Как испечь блины по-чеховски?» for details ![]() . K. Paustovsky in his autobiographical novel «Повесть о жизни/Розовые олеандры» discusses the making of куличи (a type of пирожки for Easter), and he calls the process of preparing the dough священнодействием а sacred act:

. K. Paustovsky in his autobiographical novel «Повесть о жизни/Розовые олеандры» discusses the making of куличи (a type of пирожки for Easter), and he calls the process of preparing the dough священнодействием а sacred act:

| После уборки происходило священнодействие — | After straightening up, the sacred act took place — |

| бабушка делала тесто для куличей… | Grandma made the dough for kulichi… |

| Кадку с жёлтым пузырчатым тестом укутывали ватными одеялами, | The vat with the yellow bubbly dough was covered with cotton blankets, |

| и пока тесто не всходило, нельзя было бегать по комнатам, хлопать дверьми и громко разговаривать. | and until the dough rose, we weren't allowed to run through the rooms or slam the doors or talk loudly. |

| Когда по улице проезжал извозчик, бабушка очень пугалась: | Whenever a drayman passed along the street, Grandma would get really nervous: |

| от малейшего сотрясения тесто могло «сесть», и тогда прощай высокие ноздреватые куличи, пахнущие шафраном и покрытые сахарной глазурью! | the smallest vibration could make the dough fall, and then it would be goodbye to the tall, spongy kulichi, redolent of saffron and covered with sugary glaze. |

I myself remember the same kind of feistiness over making dough for kulichi. Maybe it is because kulichi are for Easter, and because of the religious connotation, extra care was needed. Usually for regular pirozhki it is much less demanding! Kulichi don't have a filling; they are made in oval molds and have raisins inside. Pirozhki have the filling, as I mentionned above, and here each chooses each own! My all time favorites are two kinds: pirozhki with eggs and green onions, and pirozhki with apples. One has to boil a few eggs, and then finely chop them with green onions, and add salt and pepper. For the kind with apples I stew finely chopped applles with water and sugar for about forty minutes, making sure they stay moist, adding water if necessary, and then put them in pirozhki. The last trick (but not the least!): do not forget to baste your pirozhki with egg (beat one egg with a whisk for basting) before baking, it will add such glamour to your pirozhki that they will be hard to resist, just like in that picture! Actually, the pirozhki in the picture I made myself for a party at my house, they turned out very delicious, and everyone liked them!

Good luck with making your own pirozhki, and

ПРИЯТНОГО АППЕТИТА ! ![]() BON APPETIT !

BON APPETIT !

Лосось

The other day an anonymous querent wondered about the correct way to say “Thanks for the salmon!” The answer is: that depends.

If you mean that you are grateful for an entire salmon, then the word you want is a masculine word ending in a soft sign: лосось. If you mean that you are grateful for a filet of the fish which you intend to consume as food, then the word you want is a feminine word: лососина. Thus:

| Спасибо за лосося. | Thanks for the [whole] salmon. |

| Спасибо за лососину. | Thanks for the salmon [flesh]. |

Actually лосось can also mean simply the flesh of the animal, but every once in a while you will meet some pedant who will want you to distinguish the two words.

In the US one associates salmon particularly with the the states of Alaska, Washington, and Oregon. In Russia Камчатка is the major нерестилище of salmon. A нерестилище “spawning ground” is a place where fish lay their eggs.

<< 1 ... 8 9 10 ...11 ...12 13 14 ...15 ...16 17 18 ... 21 >>